| V The Eighteenth Century. Song and Choir Literature | CONTENTS | VII Popular Song-writers. Erkel and the Romantic National Opera |

{53.} VI

The “Verbunkos”.

The National Musical Style of the Nineteenth Century

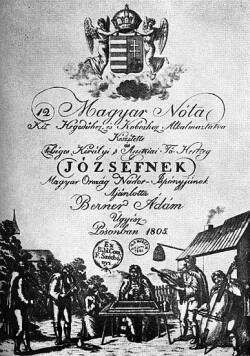

The “musical map” of Hungary in the course of the eighteenth century, especially between 1720 and 1820, showed most peculiar extremes and most radical changes. Nothing but foreign orchestras, and foreign composers, conductors and virtuosi: Joseph and Michael Haydn, Zivilhoffer, Werner, Dorfmeister, Krommer, Albrecthsberger, Dittersdorf, Czibulka, Zimmermann, Druschetzky, Wratnitzky, Franz, Roser, Pichl, Weigl, Mederitsch, Tomasini were to be found in the residences and in the towns, in the court of prince-primates and aristocrats of Pozsony (Esterházy, Batthyány, Grassalkovich, Erdődy), of Kismarton (the Princes of Esterházy), of Nagyvárad (Bishop Patachich), of Kiscenk (Count Széchenyi), of Vereb (Végh), of Pest, etc. Practically only Czech and German names were to be found in the field of musical pedagogics, among the makers of musical instruments, the publishers of musical works and the music shops. In Pest-Buda – where the fraternity of the Buda musicians was already formed around 1719 – the first music school was opened by Georg Nase (1727), the first organ maker, known by name, was Johann Staudinger (1743), the first music shops were owned by Weingand and Köpf, and the first manual for the piano was written by Franz Rigler (1779, 1798), etc. The title pages of publications of “verbunkos” and “Hungarian tunes” (i.e. dance pieces) were for a long time headed by German names – and yet this rising literature, in its spirit, was essentially different from the former work of German musicians in Hungary.

These composers, arrangers, teachers and virtuosi of smaller or bigger calibre indetified themselves with a new programme. They wished to serve the Hungarian national culture, in spite of their foreign origin. This new definition of national culture was a fundamentally new phenomenon and it was brought about by profound political, social and spiritual changes. The rising resistance to the Germanizing endeavours of Emperor Joseph II had a share in it, as well as the French revolution and the popular tendency {54.} emerging in Herder’s wake, and early Romanticism even. The foreign musicians in Hungary wished to participate in the efforts to express in Hungarian music the peculiar character of the nation and thus, together with the Hungarian musicians, determine the distinctive style of this national character. These endeavours were indentified with the new ideals of bourgeois progress and national independence, in order that their possibilities could be developed and realized. Their most characteristic expression is found in the “verbunkos” music.

Around 1760 the “verbunkos” appeared, the characteristic accompaniment of the recruiting ceremony. The “verbunkos” sources, not yet comopletely known, include some of the traditions of the old Hungarian popular music (Heyduck dance, swine-herd dance), certain Levantine, Balkan and Slav elements, probably through the intermediation of the Gipsies, and also elements of the Viennese-Italian music, coming, no doubt, from the first cultivators of the “verbunkos”, the urban musicians of German culture. A few early “verbunkos” publications and the peculiar melodic patterns found in the instrumental music of all peoples in the Danube valley, show clearly that the new style owed its unexpected appearance to some older popular tradition. The abyss of centuries was suddenly bridged over and the bourgeoisie hurriedly and with enthusiasm took over something from the lower social strata. The language of the “verbunkos” was full of national characteristics, that is of melodic turns accepted all over the country, and the “verbunkos” stood as a symbol for all this. Its support meant association with the Hungarian people. And indeed, it was here that the decisive turn took place. At the end of the eighteenth, and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, the towns opened their doors to the new Hungarian music. They surrendered to it, acquired the knowledge of the new language and placed their Western performing ability and cultural forms into the service of Hungarian music. The place of origin of the new style was difficult to locate because when we learned of its existence at the first time it was already gaining ground in the towns, in the Gipsy bands or in the hands of Western musicians. Haydn, and even Mozart had turned their attention to it, just as Dittersdorf, and later Beethoven, Weber, Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms and others. (The Gipsy episode {56.} in Mozart’s Violin Concerto in A major may be quoted here, as well as Beethoven’s König Stephan, and some parts from the Third and Seventh Symphonies, Schubert’s Divertissement, Haydn’s and Weber’s Hungarian rondos, Brahms’s Hungarian dance series, etc.; each of them memorable in the history of Magyarism in the works of Western composers.) Everything known abroad since 1780 by the name of Hungarian music consisted without exception of the music of the “verbunkos”. It was very easy to recognize because it very soon developed a complete set of characteristic elements, the cadence-pattern called “bokázó” (“clicking of heels”, a type of the medieval “cambiata”), the “Gipsy” or “Hungarian scale” using the interval of the augmented second, girlands of triplets, alternate “slow” and “fresh” tempi, widely arched, free melodies without words (“hallgató”) and fiery (“cifra”) rhythm – all these were the sings of an early matured style. This style – instrumental flexibility, a Western ability of form-building, sharply divided but widely arched melodic pattern, a striking and extensive set of rhytms – raised the new Hungarian music above other Hungarian stylistic tendencies. It should be added that from the beginning this music could count on powerful allies, namely on an almost irresistible art of interpretation. The tradition of performance of the “verbunkos” was undoubtedly developed in the music of Gipsy bands. For the member of the provincial lesser nobility, who gladly amused himself listening to a “melody without words” (“hallgató-nóta”), and later to some “czardas”, it was the ideal narcotic, pliant, readily adapted to personal demands, orientally ornamented, performed as it was by Gipsy bands, in the dreamily free and capricious sparkling of extempore ornamentations and paraphrases. We must not forget the inimitable versatility of the gipsy performer. It was characteristic that at the first performance of the Hungarian theatrical company in Pest-Buda in 1790 the music was played by the Gipsy band of Nógrád and that Hungarian theatrical performances continued to need the cooperation of Gipsy musicians. And it was the Gipsy musicians who popularized the new music – in the village, in the Hungarian small town, and even in the Western metropolises.

The foreign elements of the early “verbunkos” were absorbed, and shaded over, at least in common knowledge. When around {57.} 1800 the leading role of the new dance music was taken over by János Bihari, János Lavotta and Antal Csermák* its melodic and rhythmical enrichment was such that the “verbunkos” immediately became the most important expression of the Hungarian musical Romanticism. It even assumed the role of the representative art of nineteenth-century Hungary, the role of national music. {58.} János Bihari, who formed his well-known band around 1801 the Pest, poured popular and ancient Hungarian melodies into in framework of the “verbunkos”. He left eighty-odd compositions. In his “Kuruc” and popular song-paraphrases he was undoubtedly the most significant initiator and closest to the people. Although only a self-taught Gipsy, he was the incarnation of the musical demon of fiery imagination. It was no accident that he was credited around 1815 with having written the Rákóczi March, which in reality had taken shape under the hands of unknown musicians from old fragments, mostly from those of the instrumental Rákóczi-tune. That ecstatic bouyancy that is part of his dance music and of that of his successors, was up till then unknown in Hungarian music. János Lavotta, the conductor of the Hungarian theatrical company at Pest-Buda in 1792–93 and at Kolozsvár in 1802–1804, put together programme music from the “verbunkos” {59.} music for the first time (Nota insurrectionalis hungarica, 1797). Antal Csermák, the solo violinist of the Pest-Buda theatrical company in 1795–96, composed, together with Lavotta, Berner and others, sets of dances for chamber-music ensembles for the first time, thus becoming the pioneer of Hungarian chamber-music literature. All three were excellent virtuosi of the violin, and especially Bihari played with a fascinating gusto. They led a driven, magnetic-like existence, always on the way between Pozsony and Kolozsvár, Veszprém and Tállya; they were the restless spirits of their time, nevertheless succumbing finally to the numbing indifference of their surroundings.

This was the time, however, when there was a decisive change in the field of performance. As soon as the towns were willing to admit the “verbunkos” music, it was the public performance, the concert, first of all, that was established to serve the interest of the new music. Pozsony was already acquainted with concert life. Rigler gave a recital there in 1777, Hummel and Beethoven in 1796; while in Pest-Buda – where the long line of concert performers had been started by Tomasini, Lasser and Beethoven (1800) among others – the Musical Academy of Lavotta (1787) and of Csermák (1795) were performed there early on. At the Pest-Buda concerts the Hungarian public became acquainted with the great Viennese classics of the era. Haydn himself conducted the performance of his Schöpfung in Buda (1800). And, what was probably even more important, the theatres in the towns were opened at the same time. The Italian and German opera companies, active in the eighteenth century in the towns of Pozsony, Kismarton and Nagyszeben, performed as a matter of course only the best of foreign opera music for their aristocratic public. However, at the close of the eighteenth, and in the first decades of the nineteenth centuries the German theatrical company in Pest-Buda included in its repertoire works which showed the way and set an example to the slowly unfolding Hungarian opera. Mozart’s Seraglio was performed in Pest in 1791 (1788?), The Magic Flute in 1793, Figaro in 1795, Don Giovanni in 1797, Beethoven’s Fidelio in 1816, Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia in 1820, Weber’s Freischütz in 1822. It is worthy of note that these operas were performed so soon after their German and Italian premières. Since they were performed {60.} in a foreign language, they could hardly reach wide circles of the Hungarian public, but certainly had agreat stimulating effect on the musicians. The first performances in Hungary of the operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Auber, Meyerbeer and Verdi followed in a surprisingly rapid succession their premières abroad. It was through them that the Hungarian urban public was more closely connected with the Italian and French than with German music in the first half of the nineteenth century. This contact was also reflected in the early Hungarian opera music.

There were the lyrics of school dramas and Hungarian interpolations in some German operas since the end of the eighteenth century. These are the direct predecessors of the Hungarian music drama. The first were especially significant, because they gave voice to the Hungarian folk song on the scenes of the Piarist School in Beszterce, the Pauline School in Sátoraljaújhely and the Calvinist School in Csurgó. At the end of the century it was to a certain extent the practice of the “verbunkos” movement and partly the example of foreign operas that had a stimulating effect on the Hungarian musical theatre. Its real difficulties were not yet evident and no doubts were voiced about them. On the contrary, their appearance was welcomed with general patriotic rejoicing. We do not yet know the music of the first Hungarian musical drama-experiments – the compositions of József Chudy, Gáspár Pacha and of others from Pozsony, and among them that of the “first Hungarian opera”, chudy’s Prince Pikkó and Jutka Perzsi (Buda, May 6, 1793), the text of which was translated by Antal Szalkay from Philipp Hafner’s spectacular “oriental” magic comedy, Prinz Schnudi und Prinzessin Evakathel. Chudy’s stage music, as described by contemporary critics, “moved the heart with its melodic naiveté and pleased the ear by its harmonies”. It was composed, as far as can be established from the libretto, according to the practice of the Viennese musical popular play, the “Zauberposse” (magic comedy), and it included Hungarian interpolations; the text-book has lyrics “to be sung to the tune of a Hungarian song” or “of a fresh Hungarian song”. These occur mostly in scenes based on virtuoso effect, just as in the German plays with lyrics played in Pest-Buda which Chudy had had the opportunity to see. This conspicuous role of foreign elements accompanied Hungarian {61.} opera all through the nineteenth century. The first Hungarian musical plays, the music of which also survived, are the following: György Csernyi, Gábor Mátray’s popular pklay (1812, libretto by István Balogh), Béla’s Flight, an opera by József Ruzitska (conductor in Debrecen, later in Kolozsvár, composed to the libretto, based on Kotzebue’s German by János Kótsi Patkó), Simon Kemény of the same composer (adapter from Károly Kisfaludy’s play, both performed in Kolozsvár, 1822), King Matthias’s Elections by József Heinisch and György Arnold (1832–34), András Bartay’ Aurelia (1832) and The Ruse (1839), Márk Rózsavölgyi’s The Treasure-hunters of Visegrád (1839), etc. All these clearly show the blending of different musical traditions. Dramatic scenes of bigger proportions came from the repertory of opera music in Italian and Viennese style (Rossini, Bellini, Mozart), but idyllic, lyric and heroic episodes were always composed in the style of the “verbunkos”. This duality of method, as is well known, can be distinctly felt even in Erkel’s operas. But it should not be thought that the public regarded this stylistic duality as a deficiency, or that for this reason these compositions lost something of their Hungarian character for the public. The series of triumphs all over the country, in the twenties and thirties of the nineteenth century, of Béla’s Flight (right up to József Heinisch’s adaptation of 1837–38), proves convincingly that the Hungarian public regarded Ruzitska’s work as the incarnation of Hungarian opera, even though in it the Hungarian, the Italian and the German musical idioms stand side by side, or even merge into one another, in a most peculiar way. The secret of success may be explained by the fact that “verbunkos” music, having in the meantime gained popularity all over the country, made its appearance on the stage as well in these compositions, and the time came – around 1860 – when it prevailed in the entire language of the opera.

Indeed, the spreading of the “verbunkos” after 1830 should not be looked for in dance-music literature alone. It rapidly gained ground in chamber and piano music, in song literature and on the stage. Already at the end of the eighteenth century it was regarded as the continuation, the resurrection of ancient Hungarian dance and music, and its success signified the triumph of the people’s art. The most voluminous collection of “verbunkos” music was {62.} published between 1823 and 1832 and edited by Ignác Ruzitska, the “regens choir” of Veszprém: Magyar Nóták Veszprém Vármegyéből (Hungarian Tunes from the County of Veszprém), including 135 dance pieces in 15 “fogás” i.e. fascicles. Nobody was interested around 1830 as to whether the “verbunkos” actually continued the oldest Hungarian traditions or not. So what were its sources and where did it come from? Musicological research at its very beginning, represented by Gábor Mátray, between 1829–32 drew up the first summary of Hungarian musical history in the review Tudományos Gyűjtemény (Scientific Collection). Later on, together with István Bartalus, he began the analysis of musical documents but did not answer this question. When Gusztáv Szénfy, about 1860, in his hazy and erratic, but at the same time often illuminating writings, attempted to assess the question of “verbunkos” literature, they produced consternation and mistrust {63.} rather than serious discussion. Around 1835 Márk Rózsavölgyi,* a well-known and outstanding violin virtuoso, became the leading dance composer and for more than a decade headed the stylistic endeavours of the late “verbunkos” and of the slowly (since 1835) developing “czardas” literature. It appears that this cultivated artist was one of those composers who took the initiative in the transformation of the “friss verbunkos” (quick dance) into the “czardas” and also in its popularization. His centre of interest, however, lay in the melodic refinement of dance music and in its adaptation into the more illustrious and Western sociable idiom of drawing rooms (“körmagyar”: Hungarian ballroom dance; the successor of the French quadrille). He was one of the most accomplished masters of the cyclic dance composition. The “czardas” literature, a dance music which in form and rhythm was developed directly from the late “verbunkos”, was for some time (in the fifties and sixties of the nineteenth century) in the centre of popular Hungarian instrumental music. The part that society music played at the time of Absolutism was a parallel to the popular choral movement of the period. This “czardas” literature was, however, growing rigid and standardized already in the seventies and eighties and by the end of the century had become very trivial. “Verbunkos” music had by this time already outgrown the limits of dance music and its influence was felt in every aspect and every accomplishment of Hungarian musical life – in the romantic opera, in symphonic music, in the new popular song and choir literature. Its impact was gradually extending in the course of a century. The period of the “early verbunkos” (1788–1810) led to the period of the “culminating verbunkos” (1810–1840), which subsequently gave way to the period of the “late verbunkos” (1840–1880). And if the “verbunkos” seemed to be at first the ancient national music of the Hungarian people, it appeared now to be the music of the coming, growing nation as well, representing the birth of “Hungarian world-music”. Since the cultural significance {64.} of Hungarian music was recognized it became a matter of national importance. But on the other hand, illusions of a great perspective were, from the outset, linked with the “verbunkos”. On the day these illusions disappear from the life of the nation, the music of Hungarian romanticism will also fade away.

| V The Eighteenth Century. Song and Choir Literature | CONTENTS | VII Popular Song-writers. Erkel and the Romantic National Opera |