| VII Popular Song-writers. Erkel and the Romantic National Opera | CONTENTS | IX Late Romanticism. The Transition Period. Western Reaction at the Turn of the Century |

VIII

The Instrumental Music of the Romantic Period.

Liszt and Mosonyi: the Programme of Romanticism

The composers who realized the romantic ideals of Erkel’s period in the field of instrumental music were the representatives and (in Liszt’s case) the heroes and leaders of the universal trends of European Romanticism. Erkel’s life-work, the national opera, was organically completed in the field of instrumental monumental musical forms by Liszt’s and Mosonyi’s activities. They approached Hungarian music as adherents of different cultures, endeavouring to raise it to a high artistic level. They did not recreate this material from within, but inspired by ideals from without, in a romantic-idealistic way. Ferenc Erkel was inspired by the Italian-French opera, Franz Liszt by French Romanticism, Mihály Mosonyi by German Classicism, and they solved their problems according to these three tendencies. Erkel’s Italian-like melodic abundance and theatrical fantasy went along towards the creation of Hungarian heroic opera, Liszt was inspired by the burning revolutionary spirit of French Romanticism to the bold reform of symphonic, church and piano music, while Mosonyi, although the follower of German idealist humanism, built up classical forms on the one hand and pursued profound and diverse educational activities on the other. They are thus, all three of them, “occidentalists”, but the influence of their movement on Hungarian music is unsurpassed even by their successors, because in addition to their individual abilities they bring about an unprecedented artistic intensification {73.} of the Romantic musical idiom, which is practically consumed by this extreme passion. Their programme and their work with its Hungarian character reaches its culmination between 1850 and 1880. Their programme: the development of Hungarian music into “universal art”, “world idiom”, with the help of Western means of expression, within the range of European culture. It is in the spirit of this programme that the Hungarian works of Liszt and Mosonyi were born.

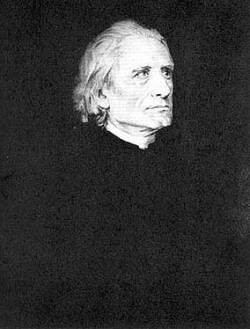

Franz Liszt* was one of the spiritual leaders of his time, the founder and master of modern church and piano music, the revolutionary genius, who swept all over Europe and conquered all concert halls of the world, whose burning imagination lent a bold and novel sense to every form. He declared himself part of the Hungarian culture, not only when he was welcomed home with ecstatic celebrations, not only by his recitals in Pest, Pozsony, Esztergom, Kolozsvár or as President of the Academy of Music in Budapest, but also in his most intimate confessions, said that he belonged with every fibre to his native country, although he never spoke its language. In his monumental artistic programme – that awakens an up till then unknown tone of heroic splendour, revolutionary fervour, dramatic pathos and burning rhetorics in the music of European orchestra, choir and piano literature – an important role is given to the voice of his native country, to the Hungarian musical material as well. His artistic development may be divided from this point of view, as shown by recent researches, into three periods. In the first phase he was interested in the possibilities {74.} of external development of the ready-made popular music material, in the second phase he used this material for the creation of great forms and novel harmonic experiments, and in the third phase he arrived at a special idiom for the presentation of his personal problems, old age and solitude. The Hungarian musical material at his disposal was not really genuine, since – as is known – he had no opportunity to become acquainted with real folk tradition (the plans of his youth in this connection were never realized) and therefore he had to content himself with the music received through his friends: the often third-rate, current material of the “verbunkos”, the “czardas” and the popular song. He was fascinated not only by the decorative externals of this music, as in the Hungarian Tunes and Rhapsodies (1840–1886) composed mostly on the basis of “verbunkos” compositions and popular melodies, but he penetrated into the meaning of this musical material in his Hungaria (1856) – written in reply to Vörösmarty’s Ode to Liszt, – in The Legend of St. Elizabeth (1865) and in the Mass of Esztergom and especially in the Coronation Mass (1855, 1867). He evoked its most profound, most elementary possibilities, especially in those sombre, demonic late works, where he compelled this impersonal national style into visionary and ecstatic eruptions. In these late creations the old revolutionary Liszt holds out his hand to the young revolutionary Bartók, bridging the gap of a whole generation (Hungarian Portraits 1870–86, Sunt lacrymae rerum in the cycle Années de pèlerinage 1869–72, Csárdás macabre 1881, Csárdás obstiné 1884). After the appearance of his book about the Gipsies, proclaiming the Gipsy myth against Hungarian music (1859) he was for a short time unpopular in Hungary; but in the sixties he was again fêted with the same enthusiasm and devotion which he had formerly received from the spiritual leaders of the country. Just like Petőfi, as a young man he disregarded frontiers; just like the spirited artists of his foster-country, Victor Hugo and Delacroix, he taught European art the new idiom of unbounded passion, and lastly, like Händel or Gluck, he became one of the greatest cosmopolitan geniuses of his time. From now on Hungary was only one of the stations of his astounding career. His initiations, however, leave ineffaceable traces in the Hungarian musical culture. His example {75.} pointed the way for the new symphonic literature, the modern piano music and piano teaching in Hungary. Thus Liszt’s work was a landmark in the history of this young, still hardly organized musical culture, and nothing that followed could ever return again into the state that had preceded his appearance.

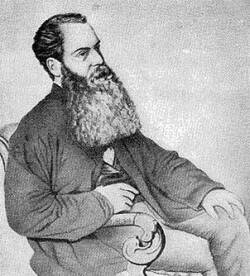

{76.} Erkel and Mosonyi, compared with Liszt, represented the type of artist who moved within more narrow confines, and were, at the same time, of a more resigned character. Nevertheless, all three shared the same fate of being neglected and forsaken at the end of their lives. We can observe in Liszt’s body of work how the enthusiasm of the Romantic artist, the versatile, restless passion of one of the spiritual leaders of the period, and his ardent eloquence was turned into more and more arduous problems of solitude. This change was even more striking in Erkel and Mosonyi. In the second half of the century the world around them seemed to sink and to become humdrum and indifferent. Without doubt, after the “compromise” of 1867, in which the ruling classes of the country, in league with the ruling classes in Austria, confirmed the semi-colonial state and dependence of Hungary, and opened up the way to rapid and artificial capitalism – the best part of Hungarian music lost its connection with the important problems of the nation, and its greatest masters were isolated. Mihály Mosonyi* from a certain point of view complemented as well as opposed his great contemporary, Liszt. He started out from an international standpoint and developed towards national aims. A meditative lyrical character, less active than Liszt, nevertheless he was, first as a music teacher to aristocratic families, then, after 1860, as the chief correspondent of the Zenészeti Lapok (Musical Journal), the most significant Hungarian spokesman of the European movement of Neo-Romanticism and attained a leading role and an ever growing authority in Hungarian musical life. In his orchestral, piano and choral works we find possibly the noblest and the most mature products of the romantic-national musical culture, a late flowering of the “verbunkos” music (Funeral music for István Széchényi 1860, Festive overture 1861, The festive purification of the Magyars at the Ung cantata to the words of Kazinczy {77.} 1860, The victory and sorrow of the Hungarian soldier symphonic poem 1860, Hungarian children, for the piano 1860, Studies for the piano 1861). His classical German education was a comprehensive basis for his Hungarian formal endeavours. His Funeral music written at the death of Széchényi belongs to the most considerable works of Hungarian symphonic literature in the nineteenth century. Constructional, form-building endeavours, first seen in early “verbunkos” music, reached their height in the works of Mosonyi. The language of “verbunkos” made a conquest of great instrumental forms in his heroic melancholy lyrical poetry.

It was actually now that the victory of the “verbunkos” culture was complete. Operatic, symphonic and chamber music, piano literature spoke the national language, and were even built up from it. All barriers seemed to fall and the “islands” of foreign cultures were assimilated into the Hungarian community, into the people; for the greatest pioneers of the national idea had come from these “islands”. They represented the last great blazing up {78.} of the old culture of the residences. The indifference of foreign countries disappeared, for Liszt was celebrated all over the world. Musical literature freed itself from the primitive state of dilettantism; the Musical Journal (1860–75), the activity of Mátray and Bartalus, the essays of Mosonyi and Ábrányi, treated the problems of Hungarian music, past and present, on the level of European knowledge, inspired mostly by the Neo-Romantic ideals of Liszt and Wagner. The public’s surrender was also complete, for the reception of every new Hungarian work was becoming more and more general. Indeed, all great problems seemed to be solved, or the solution already on the way – this was the firm belief especially from 1860 until 1867, up to the time of the “compromise”. This firm conviction had a different meaning after 1867; “Our work is done, now we may take a rest.”

But to make this rest fruitful, zealous artists were working, building up systematic schools, co-operatives and cultural organs. Kornél Ábrányi (1822–1903), Mosonyi’s comrade-in-arms at the head of the Musical Journal, worked with untiring zeal on behalf of the centralization of Hungarian musical life. He identified himself in the seventies with the foundation of the National Hungarian Choral Society and with that of the Music Academy ten years later. Károly Huber (1828–85), piano virtuoso, song and piano-composer, author, editor, pedagogue and social agitator, the propagator of Erkel’s and Mosonyi’s ideals, furthered the cause of violin playing and male choir literature; Ede Reményi, the well-known violinist (1828–98), was one of the chief promoters in the sixties of the musical life of the capital; Imre Székely, the excellent composer of Hungarian “fantasies”, rhapsodies and folk-song paraphrases (1823–87), was one of the most celebrated pianists of the country after 1852. Székely’s artistic development, just as that of two representatives of the Liszt-school: Sándor Bertha (1843–1912) and Károly Aggházy (1855–1918), was definitely influenced by the atmosphere of the French capital. They all three travelled widely, and in their works endeavoured to bring the Hungarian romantic musical language within the range of West-European forms. (Bertha and Aggházy worked also for the stage: Bertha’s opera of King Matthias was first performed in Paris in 1883, Aggházy’s opera, Maritta, was written during his {79.} stay in Berlin and Budapest and was first performed in 1897.) And characteristically it was from this circle that the formal experiments of “Hungarian sonatas” set out, which were now brought forward by Ábrányi, Bertha, Attila Horváth and Henrik Gobbi (Volkmann’s and Liszt’s pupil), or the plan of the “Hungarian quartet” with which Reményi experimented (Fata Morgana 1861); Bertha was even dreaming of the “Hungarian counterpoint”, of the meeting of Bach with the “verbunkos”! Antal Siposs, Aladár Juhász, then Árpád Szendy and István Thomán continued Liszt’s tradition in the domain of piano playing and pedagogics, and around them were a great many composers whose influence remained within a more narrow compass (Imre Elbert, Károly Szabados, Ferenc Sárosi, Ödön Farkas and others). They were partly the eclectic followers of Western examples, and partly the followers of Erkel’s, Mosonyi’s and Liszt’s romantic-national tendency.

Although the time in which the principal works of Erkel were composed belonged to the past and Liszt’s great symphonic poems and piano works had no sequels, the zealous work of smaller artists and educators could still have grown into a movement of national significance if the historic and social contradictions of the period after the “compromise” had not come more and more into the open.

| VII Popular Song-writers. Erkel and the Romantic National Opera | CONTENTS | IX Late Romanticism. The Transition Period. Western Reaction at the Turn of the Century |