| Historical Strata | CONTENTS | Underwear |

{317.} Hair and Headdress

A large number of traditional beliefs among the Hungarian people are connected with hair. Damage to the hair signifies injury to the individual himself. That is why cutting hair off was still one of the strictest ancient punishments, even during the last century. Keeping a lover by eating a bit of his or her hair, and many other superstitions, prove its importance in peasant life.

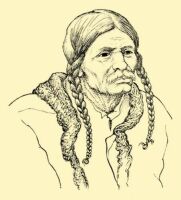

Apáti-puszta, Tolna County. Late 19th century

In the past, the hair style of men was extremely varied. Records from the 18th century mention the Palots and Cumanian areas, where many men still shaved their heads and left only a forelock on top. This old custom certainly gained strength during the Turkish rule. Even young men wore shoulder-length hair until the middle of the last century. This style went out of fashion when the young men were recruited into the army and had their hair cut, and thus short hair slowly became fashionable among the young. Older men braided their hair on two sides and then pinned it up. This style was replaced by the rounded hair style which was cut at the nape and held together in the back by one or two combs. This style could still be found occasionally among the herdsmen of the Great Plain during the first decade of the 20th century.

Boldog, Pest County

Moustaches with waxed, pointed whiskers were considered a man’s chief ornament. The moustache became fashionable during the second half of the 18th century, in spite of its being strongly prohibited by the authorities. Straight and curly styles of whiskers became usual by the beginning of this century. Such moustaches, however, have almost completely disappeared during the last decades, just as the wearing of {318.} beards, which was customary only in certain areas (e. g. Southern Transdanubia). A certain type of beard known as the “Kossuth beard” was worn in some places as a political protest, after the defeat of the 1848–49 War of Independence.

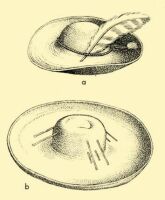

a) Hat for a cowman. Hortobágy, former Hajdú County. b) Hat with a large brim. Udvarhely County. Early 19th century

Throughout the entire Hungarian speaking area, women wore their hair long and never cut it. The name for unmarried girls was hajadon (bare-headed), which refers to their not wearing anything on their heads. Formerly girls braided their hair into two or three, and later one braid, and tied coloured ribbons into each braid. In a few places in the country girls pinned up their hair into a bun made of many small braids (Kalocsa, Sióagárd). Married women wore their braided hair pinned in a knot on the top of the head. In fact, the last act of the wedding is the pinning up of the hair of the young wife (felkontyolás).

At one time the majority of men’s head coverings were made from animal hide or wool felt. The material used for the fur cap is sheepskin, generally black in colour and peaked in shape. It is generally worn in the winter, even today. The famous Cumanian cap or cap of Tur was made of felt. Recent research proves that even during the first half of the last century this hat was worn by Hungarians all over the country, and not only by the Cumanian. It is a tall, cylindrical form of headgear, and may have come to the peasants from the old traditional soldier’s outfit. The wearing of wide-rimmed felt hats spread during the first half of the last century. We often read in the official ordinances of this time that the wearing of the wide-rimmed, so-called “peasant outlaio hats” was prohibited. Gradually the rim of the hats decreased in size. Their smaller-rimmed successors still may be seen worn on the heads of the husbandmen of the Hortobágy. The wide-rimmed hat style lasted for a long time among the Székelys and Csángós, and also among the neighbouring peoples (e. g. Slovaks). Inexpensive straw hats appeared from the middle of the last century, and became popular in certain parts of the Hungarian speaking territory especially during the time of major summer work.

The Hungarian peasant always wears a hat and does not take it off unless he is eating or is in church or some especially honoured, unfamiliar place. He is not much used to lifting it; at most he tilts it a little with his finger if he wants to greet somebody. It is such an inevitable fixture of his attire that in many places they even place it over the face of the dead. Boys and especially young men would stick the feathers of various birds in their hats. Eagle and crane feathers were primarily the prerogative of the nobility, while commoners had to be satisfied with cock or bustard feathers, up until the time the serfs were liberated. Herdsmen of the Great Plain kept the custom of wearing feathers in their hats longest. Since the beginning of the last century, the bridesmen who invite people to the wedding have worn flower bouquets or feather grass in their hats, and newly conscripted young men bind coloured ribbons onto their hats.

Kazár, Nógrád County

Kazár, Nógrád County

Kazár, Nógrád County

Kazár, Nógrád County

Kalocsa

Boldog, Pest County

The girls wear a párta, an ornately decorated headpiece on their heads, which covers the forehead but leaves the top of the head uncovered. Some predecessors of this headdress have been found in graves dating from the period of the Conquest, but many of the later type of {321.} headdresses came to the peasantry through the mediation of the nobility. The párta was worn on holidays and special occasions, and was valued as the symbol of maidenhood. This meaning is expressed in the saying that a girl “stayed in her párta”, that is to say, she remained an old maid. The most beautiful kinds of maiden’s headdresses were worn in the district of Sárköz, in Debrecen, in the villages of Kalotaszeg, and in Torockó.

Folk belief assigns greater magical power to a married woman’s hair than to a girl’s, and that is the reason why a married woman must always keep her head covered. The coif or headcovering (főkötő) serves this purpose, the shape, colour and form of which vary greatly according to region, the age of the wearer, the weather, and the occasion. Usually an under-headdress holds the bun of hair in place, and a more ornate one is fitted on top of that for festive occasions. This headdress is made stiff with some cardboard-paper. Various versions developed in the Hungarian-speaking regions. The most usual coifs are shaped like a cylinder or a column. The Matyós wear a conical coif, while in certain parts of Transdanubia the coif is formed into flat, square shape. Rules, bows, and ribbons are sewn on the front. In certain regions, after the birth of the first child, the young wife wears a red headdress, the colours becoming darker as the number of her children increases, and finally she {322.} wears the black colour befitting a grandmother. During the past decades such headgear has disappeared almost completely, having been replaced by a kerchief tied over the head, whose colours darken as the wearer grows older.

| Historical Strata | CONTENTS | Underwear |