| Outer Wear | CONTENTS | Footwear |

Mantles and Coat-like Outer Wear

It is easier to understand coat-like outer wear if we consider the most important types and those known over the widest territory according to their material. A significant proportion of garments were cut from material woven of wool, or perhaps felt, while others were made of fur or leather, among peasants mostly of sheepskin.

Kisújszállás, Szolnok County. Early 20th century

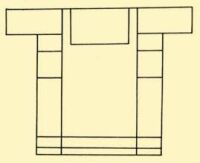

The most widespread form of coat-like outer wear is the szűr mantle. Although it has sleeves, in most places the sleeves are not used as such but are sewn up one end so that small utensils may be kept in them (cf. Ill. 37). In some places (Transdanubia), the sleeves became shorter until they atrophied completely. The word szűr itself probably originated from the first syllable of the word szürke (gray), which refers to its earliest colour. The mantle was sewn out of rectangular pieces, further proof of the great antiquity of this article of clothing.

Although the szűr was worn by men from Transdanubia as far east as the region of Kalotaszeg in Transylvania, certain regional variations can still be differentiated.

Thus in Transdanubia the szűr is generally very short, its large, square collar reaching all the way down to the waist. This collar was also used to cover the head in rainy weather. The szűr of the Palotses is of the most simple type, with little ornamentation.

Veszprém County

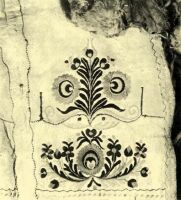

In the region east of the Tisza, and Kalotaszeg, the szűr had a short {326.} stand-up collar and was called nyakas szűr (collared szűr). Since the beginning of the last century the szűr has been richly ornamented with appliqués or embroidered embellishments, while formerly only its edges were decorated with colourful materials.

The most highly ornamented and embellished versions of the szűr were worn by young men, while married men, especially in their old age, wore szűrs decorated primarily with black. The szűr is a most expensive piece of peasant wear, yet every young man tried to buy one by the time he was ready to get married. When going to propose, he left his szűr at the girl’s house as if by accident, and watched with great trepidation the next day to see if they hung it out in front of the house. If they did, it meant he was not considered a desirable suitor. If it was not outside, however, his best men could go to the house to ask for the girl’s hand. This is why the expression “kitenni a szűrét” (to put one’s szűr out) is a vernacular phrase meaning “to throw somebody out”.

Hortobágy

Tunyog, Szabolcs-Szatmár County

Matolcs, former Szatmár County. Early 20th century

The szűr was not worn in Székelyland; instead garments called cedele (Kászon), zeke (Udvarhely), or bámbán (Csíkszék and Háromszék) were worn. These were also made from broadcloth and belong to an ancient type of clothing from south-eastern Europe. Formerly these were cut out of a single length of cloth, more recently an added bottom part was sewn into it. These garments reached to mid-calf during the last century, then gradually became shorter. They were embellished with black braid and, at certain places, edged with green or dark blue broadcloth. In earlier times there was never a collar; collars came into fashion only later. {328.} The festive cedele was ornamented more richly, with two rows of braid trim. It was worn thrown on the shoulder in warmer weather, while in the cold it was tied around the waist, usually with a belt made of horsehair.

Erked, former Szilágy County. 1916

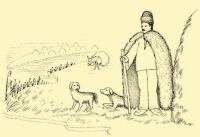

The guba is known over a relatively smaller area but maintains a close connection with the various articles of clothing of Europe’s eastern and western regions (cf. Ill. 44). It was made out of rectangular lengths of guba broadcloth (cf. p. 310), with a round hole cut for the head. The sleeves were much longer than the arm, which eliminated the need for gloves. The guba was worn in very cold weather; otherwise it was carried thrown over the shoulder. In the course of its continuous diffusion, the guba reached the line of the Danube during the 19th century, but it was never worn on the western side of the Danube. A guba may be black or gray, the former being in many places the attire of the prosperous farmers, while the latter was worn by the poorer peasants. Speaking very broadly, however, the guba was associated with less prosperous people, as indicated by the proverb “Guba with guba, suba with suba” which means that the poor should associate with and marry only the poor, and the rich only the rich. The guba was worn by both men and women, although those of the women were much shorter, reaching only to mid-thigh.

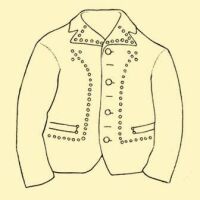

The garments mentioned above are all long. However, broadcloth was also used to make clothing which reached only to the waist or just a little past it. These broadcloth jackets could be found in different forms {329.} and colours over a large part of the Hungarian-speaking regions. In many places this jacket was called dolmány, and had a stand-up collar. In other places the collar was folded down and richly braided. Certain versions, such as the dolman-like mente, was worn thrown over the shoulders, a practice that came into use in connection with hussar costume.

Debrecen-Balmazújváros. 1740

Former Bács County. Early 20th century.

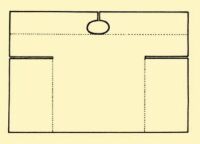

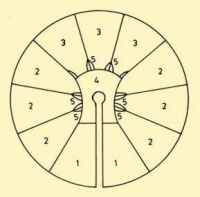

1. Front piece. 2. Side piece. 3. Back piece. 4. Shoulder piece. 5. Addition to each skin where the front legs are missing

Kisújszállás, Szolnok County

Nagycigánd, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Among sheepskin garments, the suba was worn over the greatest part of the Great Plain (cf. Ill. 37). It belongs to the category of cloak-like garments, and simple, unornamented versions of it were worn, not only by herdsmen, but also by carters and the people of the distant farmsteads. The most embellished examples were worn by the prosperous peasants of the towns. The suba protects its wearer against rain and cold, {330.} and also serves as bed and cover and, if necessary, as a table, because by spreading it on the ground one can eat from it. In the cold it is a suitable cover to spread on the back of a sweating horse. When the suba starts to get ragged, it is put in the corner of the oven, on a mean bed or on a bed in the stable, where it still provides good service.

The suba is circular in shape when spread out, as it consists of individual triangular pieces of sheepskin (cf. Ill. 37). The simplest suba consists of only 3 to 4 pieces, which were cut and sewn by the herdsmen themselves. But a very beautiful festive suba was made of 12 to 15 sheepskins and assembled by so-called Hungarian furriers, who travelled to distant fairs with their finished goods. The suba was richly embroidered, which is why an extremely high price had to be paid for it. It was meant to last for a lifetime, and poorer folk, especially day labourers and farm hands could not afford to buy one. Men’s subas are generally white or yellow, the women’s are usually brown. The people of the peasant towns of Transylvania and of Transdanubia preferred the same colours.

Debrecen

Herdsmen made the most simple leather garments themselves. The hátibőr (back hide) of the Great Plain is made of a single sheepskin, the two hind legs tied at the waist, the two front ones at the neck, so that it covers only the back. The mejjes (chest warmer) consists of two parts, {332.} one worn on the back, the other on the chest. It is held together on both sides by binding. Such a garment had no sleeves, and was only rarely ornamented. On a more elaborated version the skin was sewn up on one side and fastened on the other with buttons (Székely, Csángó). The front was embellished with rich embroidery. Men and women both wore several versions (cf. Plate XVI).

Sleeved sheepskin jackets (ujjas ködmön) are known over the entire linguistic territory (cf. Plates XVII–XIX). Some reach to above the waist, others down to mid-thigh. We find both straight cut and flounced bottom ködmön styles. The former is often so short that it does not even cover the waist (South Transdanubia, see Plate XX), although in earlier times in some places it was long enough to cover the knees (Great Plain). Women often tie a shawl under the ködmön, in which case the neck is cut out, while those worn by men often have a high neck. The type with a flounced bottom is worn mostly in the Great Plain. This type of ködmön flares out from the waist, and is thus especially suitable for riding a horse. It was often used as wear in the army; supposedly, King Matthias had 8,000 of these jackets made by Great Plain furriers in the second half of the 15th century when he was preparing to besiege the famous fortress of Southern Hungary, Szabács. The bottom and front of the ködmön jackets were trimmed with fur and those of the women embroidered richly, those of the men less so (cf. pp. 389–9).

The different kinds of sheepskin coats were made by artisans called Hungarian furriers, who were experts not only at sewing but at embroidering as well. They never worked with broadcloth. On the other hand the so-called German furriers made garments that were made of broadcloth outside and lined with sheepskin. This garment first appeared among the nobility, then it spread increasingly among the peasantry as well, especially from the middle of the 19th century.

| Outer Wear | CONTENTS | Footwear |