| Historical Strata of Ornamental Folk Art | CONTENTS | Furniture Making |

Woodcarving

(Owned by Mihály Tóth, a herdsman specialist at carving) Felsősegesd-Lászlómajor, Somogy County

From the point of view of its basic material, carving can be of many different kinds. Wood is the most suitable, but horn and bone are also carved. So far we have become acquainted with two large-scale woodcarvings: the Székely gate and the grave posts and crosses of cemeteries (cf. p. 134). Similar monumental woodcarvings can also be found on houses. Primarily geometric patterns, developed mostly by applying compasses, were carved on the main girder beam, with sarmentose ornamentation and the depiction of living creatures only appearing sporadically. Geometric ornamentation, which can be looked upon as the oldest in time, survived primarily in Transylvania and between the Danube and the Tisza. For example, in Kalotaszeg they decorate the stand of the spinning distaff with such patterns. The most beautiful examples of these were carved by the young man for his intended wife {372.} or by the husband for his new wife. If he did not possess the necessary skills the lad would turn to a master whose work he held in great esteem. In Kalotaszeg chiselled or carved geometric ornaments were carved even on hoe cleaners. This oldest style must have at one time been general through the entire Hungarian linguistic region, as is demonstrated by several mangle rollers carved to perfection in this manner which came to the Hungarian museums from western Transdanubia. Geometric ornamental form was popular throughout Europe, and is generally held to be the oldest type of decoration. Characteristically, it survived best in Transylvania, rich in wood, where the Hungarians and Rumanians know and use this ornamentation to this day. Most peasant men make these carved objects themselves, although there were popular masters who could carve especially well. Some carpenters and millers were famous far and wide for their woodwork.

Győr-Sopron County

Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Especially beautiful are relics left by windmillers of the area between the Danube and the Tisza, who not only erected complicated wooden {373.} structures of windmills, but ornamented its inside with superb carvings. Worked in relief, these are sarmentous, flowery ornamentation, with decorative inscriptions in which the names of both maker and owner can be found. Another master of wood carving is the honey-cake maker (bábos) who used to make the wooden moulds for honey cake himself. Working with a chisel or a knife, he cut the pattern with a great deal of experience and artistic sense to a depth of 6 to 8 mm. Honey-cake making itself, like the trade of bluedyeing, came to Hungary from the West and so retained in its wealth of forms many Austrian and German {374.} characteristics. The most beautiful examples are those which portray certain religious scenes, very likely on the basis of old woodcuts. Much livelier are those wooden forms that already show secular objects: a figure of a certain herdsman or outlaw, a heart, a bouquet, a hussar, a dancing pair. The numbers 3 and 8 occur often, especially on the heart shape wooden forms, the symbolic significance of which is the belonging together of a girl and young man.

Székelyland, former Csík County. Middle of 19th century

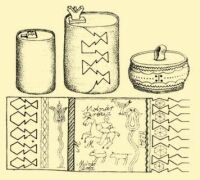

Tree bark (elm, linden, pine, birch, poplar, etc.) is suitable for making various vessels. Noteworthy among these are the small, cylinder-like salt holders, the most beautiful examples of which have turned up in Transylvania, although we also know of similar ones from Upper Hungary and Transdanubia. The bark was peeled off in ribbons and the ends cut in such a way that by rolling them and sliding one on top of the other the box would be firmly fastened. The bottom and the top are closed with wooden plugs. The sides are ornamented with carved lines and circles, the equivalents of which, along with the technique of fastening, can be found among the various Finno-Ugric peoples. Thus these containers supposedly belong to the oldest layer of ornamental folk art.

Former Ung County

From early times, herdsmen were regarded as the best carvers, as they {375.} always had more time than the farmhands working on the large estates or the peasants who worked on their own land. When they followed the stock, or when the stock grazed peacefully, the herdsman took a jackknife and a piece of wood from the bottom of his knapsack, and in a short time turned out some superb work of art. It is true that he had to do this mostly in secret, because the landlord, the bailiff, or the leaders of the village did not look favourably upon artistic herdsmen; these authorities regarded them as unreliable and were apt to send them packing. Fortunately, even the overseer got to the faraway pastures and endless meadows only rarely, so the herdsmen could keep on carving in peace. This is why herdsmen’s art still existed in the first decades of our century, even when the peasants of the villages and the farmhands had already ceased to ornament their objects for quite a while.

Hungary

The most characteristic basic materials of the carving herdsmen are wood and bone (horn). Most of the objects used by the herdsmen are made of wood: the richly decorated cudgel, the whip handle, the shepherd’s crook, the axe handle, the wooden spoon to stir mush with, the jack-knife handle, the mirror holder, the drinking vessel, the razor case, the match box, the flute, and the pipe stem. The herdsman also carved smaller utensils for housekeeping out of wood, such as the beetle, {376.} mangle, wall salt holder, and children’s toys. The horn, drinking gourd and holder for the scythe sharpener whetstone is made from horn left in its natural shape without changing it. It was necessary to saw the horn apart in order to shape smaller objects such as salt holder, mange-grease holder, and match holder.

When we consider the method of ornamentation, we find that geometric designs prevailed in Transylvania, while in Transdanubia, Upper Hungary and the Tiszántúl three clearly distinguishable styles of carving developed.

The earliest herdsmen’s carvings of Transdanubia are known from the end of the 18th century. Pieces surviving from this period have been ornamented by chiselling and are geometric in character. Such objects, on which the engraved part was smeared with soot, gunpowder, and tallow mixed with oil to emphasize the incised lines of ornamentations appeared only at the beginning of the 19th century. The sealing wax process first occurred in the first quarter of the last century. The chiselled-out pattern was widened into inward-slanting grooves with the tip of a red-hot knife, and filled with black, green, blue, and red sealing wax; then the rough surface was smoothed out with a scouring rush or a piece of glass and brushed with beeswax (cf. Plates XXIII–XXVIII). Relief carving, which tried to fill as much as possible of the given surface, replaced the sealing wax and other techniques since the end of the last century, after which time it became the most widely spread carving technique in the western half of the linguistic territory.

The herdsmen’s carvings of Transdanubia reflect their environment faithfully, and the entire world of their makers: colourful flowers, trees, bushes, and representatives of the animal world–sheep, pigs, foxes, rabbits, owls, and doves. We can see the shepherd walking behind his flock, the horseherd curbing his horse, the swineherd flashing his axe, the cattleherd parading in his embroidered fancy szűr coat, the tavern keeper and his wife, and the gypsies playing a song.

Monostorapáti, Zala County

The favourite figure on Transdanubia wood carvings is the outlaw, the betyár. The outlaws of the 19th century came from among the {377.} peasants whose land was taken from them, deserting soldiers, serfs, and peasants who could no longer bear the high-handedness of their landlords. They did not harm the poor populace; instead they often helped them:

| I blocked the roads, |

| And plundered the lords. |

| When I could take no more |

| I gave all to the poor. |

–says the ballad about Andris Juhász of Somogy County. Many outlaws fought in the 1848–49 War of Independence against the oppressors, it is therefore natural that their popular figures frequently appear not only in folk poetry, but also among the scenes of herdsmen’s carvings.

Hortobágy, former Hajdú County. 1920s

Originally the ornamentations on horns in Transdanubia were engraved and then coloured with nitric acid (cf. Plate XXIX). The ornamentation of the gourd reached a high artistic level and is related to similar work in the neighbouring Croat areas. A calabash suitable for use as a watering gourd must be carefully tended, run up on a trestle, shaped in a lath frame or glass jar, and decorated only after it is ripe. Its engraved ornamentations resemble those of wooden mirror-cases and of the horn salt holders. The herdsman tied the gourd filled with water on his belt and carried it with him into the fields (cf. Plate XXX).

Among the herdsmen of Upper Hungary the shepherds were especially great masters of wood carving. The most characteristic of their work is the drinking cup (csanak), which is tied on the knapsack of the herdsman, the hunter who walks the forest, and the peasant who tills his fields, in order to have it always on hand. The handles of Palots drinking cups are the most ornate, and often carved in the shape of a snake, dog, or sheep. The decoration shows a close relationship to work of the herdsmen-artists of the nearby Slovakian areas. The drinking cups are decorated on their sides with trees, flowers, and preferably with scenes taken from hunting, husbandry, or agriculture. Cudgels and axe handles are inlaid with lead, tin and pewter. Melted metal is poured into the carved-out, lace-like grooves of the wood, and when the metal cools, the geometric ornamentations are chiselled on the surface.

Veszprém County

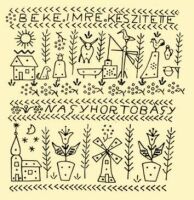

At one time it was impossible to find decent wood on the barren steppes of the Great Plain even after a day’s walking, and yet excellent remains of wood carving have survived from this area also. The herdsman generally pilfered the plum trees of the vineyards and orchards which lay outside the villages in orde to get good material for the whip handle he was making. The most widespread method of wood decoration in the Great Plain is inlay with horn, brass, and recently with plastics. They sink the carefully cut-out figures into the wood and fasten them with tiny brass nails. By this method the herdsman of the Tiszántúl, the region east of the Tisza, decorates the handle of his whip, hatchet, and axe, his cudgel, and, more rarely, certain razor cases as well. Among the ornaments we often find entire compositions depicting scenes of the herdsman’s life. At other times the objects of the herdsman’s life are scattered seemingly without any particular connection: {378.} axe, knife, fork, kettle, moon, sun, stars, gun, and pistol (referring to one-time outlaws), etc. On almost every piece the name or initials of its maker and owner are inscribed along with the year it was made.

Former Zemplén County. Second half of 19th century

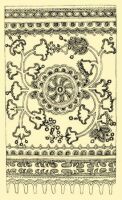

Horn and bone carving has a great history in the Tiszántúl. The herdsman carves the ornamentation with the tip of his jack-knife and often tints the more important and outstanding sections yellow with nitric acid. Part of the ornamentation of the Tiszántúl herdsman’s work is geometric, and often, though less frequently, sarmentous plants, herdsman’s objects or scenes and depictions of outlaws occur on them. In the northern part of the Tiszántúl the huge horns of the grey Hungarian cattle are lavishly decorated with floral and geometric designs. A distinct feature of these outstanding works of art is a central circular design with tendrils and flowers branching out of it. Equivalents may be found among the Slovaks and Ruthenians.

Veszprém County

The use and decoration of bone must be discussed separately, because these derive to our days from great antiquity. Geometrically patterned {380.} bone dice, and different sized beads, made of sheep or dog bone, are strung on thongs by herdsmen. The geometric engraving is blackened with soot and tallow, and even if this was not done, time sooner or later would make the pattern show up. Such bead-like ornaments have been found in graves dating from the time of the Conquest, so that we can justifiably consider this type of ornamental folk art as being of the greatest antiquity.

Transylvania, 17th–18th century

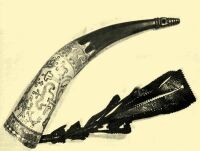

Most of the powder horns (porszaru) that have been found in the eastern half of the linguistic region imply even greater antiquity. Hunters from the 16th and 17th centuries on kept their gunpowder, which was very sensitive to moisture, in these. They were made of the two-branched horn of the stag and outfitted on the top or bottom with a removable plug, carved out of bone. Two hangers on the side indicate that the hunter wore his powder horn hanging on his waist, as does the worn condition of usually the unadorned side. We do not exactly know what may have been kept in these horns before the discovery of gunpowder, but very likely it was salt, which is also sensitive to moisture.

Eastern region of the Tisza. Second half of 19th century

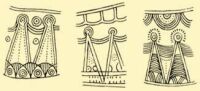

Similar implements, decorated with small central circles, have also turned up, mostly from Avar graves of the Migration Period. The circular pattern can be found on 17th and 18th century samples also. Furthermore, whole lines of designs, indicating even greater antiquity, can be discovered on these horns. Thus the swastika (rotating rose), the various forms of which are traceable to antiquity, is often placed in the centre. Especially interesting are triangular human portrayals running along at the bottom of the two branches of the horn, which, as far as the composition is concerned, is the exact equivalent of the Halstatt type of human portrayal (early Iron Age, 10th to 5th centuries B.C.). It is interesting to note that the herdsmen of southern Transdanubia carved similar figures on their wood-framed mirrors at the end of the nineteenth century. Such motifs occur on hewn chests even in our century. All this is clear evidence that the survival of certain methods of portrayal is possible not only through a few centuries, but through thousands of years. The sarmentous pattern of certain examples resembles the metal purse-plates which date from the time of the Conquest. We often find simple animal portrayals, mostly stags, alongside of which they also engraved a flag. This indicates the magic with which they tried to assure the success of the hunt.

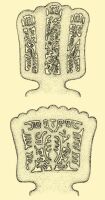

The comb maker (fésűs) is the professional master of horn processing. However, combs of great antiquity are not known, since the combmaking masters, who were organized into guilds, primarily travelled as journeymen in western countries and brought a significant part of their patterns from there. However, though they learned about their craft mostly in the West, they also got acquainted with the wealth of forms of the herdsman’s art and szűr making, introducing such patterns to western countries. The fanciest combs were worn in the hair of married women, and though men did wear a curved comb, no ornamented piece has appeared so far. The comb-making master drew the pattern on paper and copied it from there onto horn, then cut out the filigreed, diaphanous ornaments with various tools, primarily with a saw. Certain {381.} masters possessed a collection of patterns in excess of one hundred, and they continually tried to complete and increase their designs in accord to changing fashion.

| Historical Strata of Ornamental Folk Art | CONTENTS | Furniture Making |