| Furniture Making | CONTENTS | Embroideries |

Homespun

As we have already become acquainted with the production of plain homespun textiles (cf. pp. 302–9), we shall speak here only of the ornamented ones, which are also made of hemp, flax and cotton. The finest material is used for these, since ornamented homespun is the woman’s “badge”, and a number of its pieces are made for specific occasions.

Thus in the Bodrogköz, not long ago, a differently shaped and patterned homespun was attached to every significant event of human life, and in this way, accompanied man from the cradle to the grave. The marriageable girl and her mother prepared, well ahead of time, the various richly flowered homespun kerchiefs for the bridesmen, the best men, the priest, the drivers, and even for the gypsy band, in such a way as to show the maker’s skill on each piece, say by using a different pattern. They handed out over a hundred kerchiefs at certain large weddings. The young wife had already started to prepare godparent kerchiefs before the wedding to take food in when she should invite one of her neighbours to stand as godparent. Textiles woven with red were put into the crib of a child, to ward off the evil eye. A flag-like homespun, hung out on the church tower, gave notice of a child’s death. A table cover woven with black was put on the table the priest preaches from at burials. A richly decorated homespun shroud was spread on those who died young.

The basic colours of Hungarian homespun are red and blue. Only rarely and more recently has some other colour been added to these. The technique of weaving makes right-angled ornamentations possible, but it makes continuous patterns very difficult to construct. Therefore, patterns are set up in slanting angles also, and with these expression becomes easier. In spite of this, weavers have recently generally aspired to portraying naturalistic roses, dolls, beets, etc., in such a way that they can be recognized by anyone. The closer they come to this goal, the higher the accomplishment is valued.

Simple, plain peasant weaving is, relatively speaking, not very difficult, but decorative weaving is all the more so, since the material has to be picked up. Even medieval sources mention the szedett vászon (“picked-up” linen), because of its greater value. The loom is warped as for plain linen, but before they begin weaving they pick up the warp on {390.} planks according to the pattern. This has to be done again each time for as many parts as there are to the stripe or pattern. The weaver’s child also helps in this. Her task is only to make the rod behind the heddles stand up and lie down, according to the way her mother wants it.

The art of rojtkötés (macramé, fringe tying), which approaches lace in effect, is also connected to homespun textiles and to embroideries in certain areas, such as Bodrogköz, Sárköz, and among the Palotses and Matyós. The edges of tableclothes, aprons, towels, and godparent kerchiefs are decorated with hand-knotted fringes that are geometric in design and often four inches wide. Macramé frequently takes as much time as it does to weave the ornamented homespun itself.

Sárköz

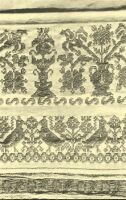

The weaving masters (takács), organized in guilds, already worked in Hungary in the 14th and 15th centuries and jealously guarded the secrets and standards of their trade. The journeymen and apprentices could become masters only if they learned every technique of weaving and proved it by a superb piece of work, the masterpiece. But first they had to go for a long journey to foreign countries, to become acquainted with {391.} all the tricks of weaving. Thus they brought back many new patterns with them, which they recorded in pattern-books and passed on within the family. These patterns made their way to the peasant women also, especially when they had the weavers weave their yarn into linen for them (cf. also p. 309).

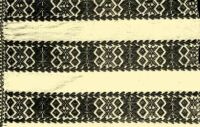

In certain areas women were excellent masters of ornamental patterned weaving. The women of Sárköz were especially adept, and people from other villages turned to them eagerly for patterns or even for finished homespun. Before the turn of the century they used mostly flax and hemp yarn that they had made themselves. From then on cotton, which had already been used earlier for the weaving of patterns, gained ground increasingly. At first only red was used, to which later came a few supplementary colours. Wider and narrower stripes follow each other on the design, the plain weaving in between emphasizing the pattern well. The stripes themselves do not end rigidly but playfully merge into the white background, their edges loosened up by some patterned detail. Stars, flowers, little birds, surrounded by geometric designs, often figure among the pattern. The ornamental homespun were used mostly on the bed, made up into pillows, and on towels and kerchiefs. The tablecloths are the most ornamental, being entirely covered by designs. The weaving of Sárköz began to decline between the two world wars, but in 1952 a weavers’ co-operative was formed in Decs, and its members, have created a new style.

In the southern part of Transdanubia, Somogy and Baranya were equally rich in homespun. Several nationalities live together in the latter area. The patterns used by the South Slavs on woollen homespun differ from the homespun of the Hungarians which are made of flax and hemp and decorated with red and black. They make tablecloths, aprons, and towels out of these. From the beginning of this century the older geometric designs–flowers, leaves, stars–were transformed into naturalistic ones. Patterns were arranged in stripes, the free area left plain, almost white in colour, which emphasized the richness of the homespun even more.

Somogy County

{392.} Weaving is very much alive to this day among the Palots, the largest and most widely spread ethnic group. Their work is the same in regard to material as the previous ones and differ perhaps only in that in some places woollen yarn was also used. Blue, green and pink colours have also spread alongside red. Such stripes, as they alternate, have a very special colour effect. They are placed at a relatively greater distance from each other, so that these forms make up a homespun different in character from the previous ones. Pillows and different kinds of kerchiefs are made from the woven material, primarily aprons from the ones with a geometric design. The co-operative that works in Szécsény and Heves further developed the old patterns and makes this Hungarian homespun, which is one of the most beautiful, famous far and wide.

Baranya County

The homespun of Bodrogköz is looser in construction than the ones mentioned above. In order to demonstrate the richness of the patterns, it is worth mentioning the following among the many designs: birch tree, cherry, pine tree, shamrock, rose, flower, beet, frog, June bug, rake, {393.} candle, small pipe, chain, clock, fritter, doll, star, buckle, etc., all well carried out by the weaving women. The way these are juxtaposed is so typical of certain weaving women that for decades afterwards the maker can be recognized from it.

The designs of the Szabolcs and Szatmár homespuns are also red, the white background appearing among them only rarely. They weave the pattern so close that certain ornamental elements are harder to differentiate. Thus the composition becomes more unified. They usually piece together two widths in the centre to make a square tablecloth out of it.

Baranya County

Weaving is alive to this day among the Hungarians of Transylvania, but here the importance of wool, along with flax and hemp, is especially great. The Székelys of Kászon still weave linen out of pure hemp, cotton, or a mixture of the two, into which they put striped patterns with motifs of a plate, star, rose, flower, bird, oakleaf, cockscomb. In the last century, the design was still made exclusively in red. Blue also appeared at the end of the last century, the two colours were not mixed until the 20th century. The motifs varied on pieces made for daily use: pillowcases, featherbeds, handcloths, and children’s sheets. Occasional and {394.} special pieces were woven in a particularly ornate fashion. Such are the best man’s kerchief, the baptismal sheet, the cloths to hang on a rod in a room, the ornamental pillow cover, the wedding tablecloths, etc. Their designs in many cases resemble that of medieval cloths called bakacsin.

Nógrád County

Székely of Bukovina, Transdanubia

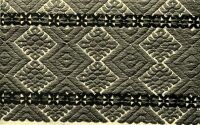

According to our present knowledge, the majority of the Magyars of historical times did not weave rugs; we find these only in Transylvania. The warp of the Székely rug, or a kind of rug called festékes (dyed), is hemp, while its weft is home-dyed wool. This stands very close to those Eastern European rugs which, among others, are used practically to this day by the Russians, Ukrainians, and Rumanians, although the connection can be traced even further. These all are similar in that the majority of their designs are geometric, as a result of their weaving technique. Székely rugs spread throughout Transylvania in the 17th and 18th centuries, and we often find them mentioned in the inventories and last wills of this era. The dyed rug, however, differs from its neighbours in colour and arrangement. It is made with relatively few colours, and with pleasing geometric designs. Reserved modesty generally characterizes {395.} it, perhaps precisely because it belongs to the earliest layers of folk art.

In Kászon, a region of Székelyland, they are still weaving the dyed rug, partly for their own use, partly to sell to their neighbours in Háromszék, where it is no longer made. The oldest known samples originate from the middle of the last century, and these are characterized by muted colours. They got the dye for the tobacco yellow (greenish ochre) and Indian red basic colours from plants and flowers grown on the mountainsides. They mixed this with raw-wool and blue-coloured yarn. More recently flaming red and green are often used as well as a combination of red and black, although naturally these are not coloured with plant dyes. Geometric patterns are composed into units of various sizes, such as the large rose that fills the entire centre of a rug, or four small roses, the centre motif of which is framed by ornate lines. Such rugs were originally used for covering the bed in such a way that they reached to the ground. More recently they are also used on tables, or to decorate the wall.

| Furniture Making | CONTENTS | Embroideries |