| Folk Tales and Legends | CONTENTS | Fairy Tales |

The Folk Tales

CHAPTERS

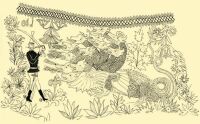

A design from a swineherd’s horn.

Tolna County. 19th century

The Hungarian word mese is an ancient inheritance from the Ugric period; it can be found both among the Voguls and Ostyaks, with the basic meaning “tale, legend”. The “e” sound at the end of the word is either a possessive suffix or diminutive suffix, which developed separately in the Hungarian language. The word mese appeared at the end of the 14th century, when riddles were marked by this word, which also proves its antiquity. The word occurs more generally from the 15th {553.} century, meaning “narrated, imagined story, a parable, an enigma”. In the 1533 dictionary of Murmelius, the translation of fable is still beszéd (i.e., “talk”), and with this definition he differentiates it from história (history), which he translates as “true event”, making a distinction between the “lying” fable and real history. The present meaning of mese developed only in the 18th century, thus following the same path as other European languages, i.e., by being restricted to signifying a particular genre.

Before turning to the discussion of Hungarian folk tales, let us take a quick look at its most important general characteristics.

{554.} Especially if as collectors we sit down next to the story teller in some village where the practice of story telling still exists, and listen for long hours to adventures and tales, our first surprise will be that nothing unbelievable takes place in the stories: everything is in its place and seems absolutely necessary, reflecting things as they should be. This sounds strange at first hearing, but it is true. Only an uninitiated person, the one who is left out of the magic circle of the tales, views the adventures happening to the heroes–to young swineherds or to princesses–as an impossible miracle. Naturally, to the unbelieving listener who thinks only in terms of this world of reality, the transformation of the fugitive pair of lovers into a lake and a duck swimming on it, the misleading of the wicked pursuer, the little prince who turns into a fawn, the princesses in the castle rotating on a duck’s foot, carried away by dragons, all these occurrences are totally improbable and miraculous. But those who listen to the tales, or read them with true identification, do not observe a special emphasis, a stressing of the miracle, when these miraculous parts are told. In tales on the lips of the people, the miracle is a natural element of the story; only on the literary level does it become a strange, or romantically emphasized detail.

| Folk Tales and Legends | CONTENTS | Fairy Tales |