| Family Organization | CONTENTS | Artificial Kindred, Neighbourhood |

{67.} The Troop, Clan, Kindred

The nuclear and extended family is an economic unit bearing the same name, which in the majority of cases lives on the same plot of land, in the same house. On the other hand, the clan (nemzetség) or the troop (had) do not belong together economically. Tighter and looser ties are indicated by a common family name, by a careful recording of descent from the same paternal ancestor, and by the defence of their mutual interest. It is very difficult to differentiate between the clan and the troop, because in some cases they are only synonyms for the same thing appearing in different regions, while in other places where they live next to each other certain differences are observable between them. Generally speaking the clan consists of a larger, the troop of a smaller unit.

The nem, nemzet, nemzetség (clan) is the name for an institution of kinship comprising several nuclear or extended families regionally, but not infrequently within the same territory as well. We can trace its existence, in the case of the nobles, right from the Conquest, and for serfs from the 16th century, when family names became increasingly fixed. This, however, does not mean that it was not generally known much earlier.

The clan was maintained through seven generations in the old days, but this number steadily decreased in the last century, until in more recent times it has extended only through three generations. The living and the dead alike are included in the clan, generally extending from great-grandparents all the way to third and fourth cousins. The old members of the clan kept track of all this, and we know one Székely from Bukovina who listed by name 273 people who belong to and have belonged to his clan. The Magyar clans were strictly exogamous, that is to say, they did not permit marriage within their ranks. This prohibition became more and more limited as the boundaries of the clan narrowed, and later extended only to second cousins. The wife usually did not belong to the clan of the husband but kept her own. Her connection with it was shown in the first place by the retention of her maiden name in village usage. Her clan provided a defence for her if she suffered some grave injustice from her husband. The theory of patriarchal seniority asserted itself vigorously within the clan, so that the oldest, most respectable and wealthiest members held it together. Because the role of the clan in peasant societies differs according to region or group, instead of generalizing, we shall give as specific instances two archaic forms from the eastern half of the linguistic region.

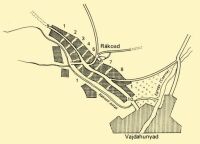

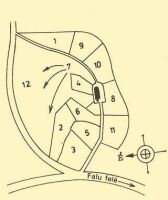

Rákosd, former Hunyad County. Early 20th century

1. Recent settlers, 2. Bertalan, 3. Jakab, 4. Balázsi, 5. Dávid, 6. Farkas, 7. Gergely, 8. Pető families, 9. Upper village 10. Lower village

Rákosd, former Hunyad County. Early 20th century

1. Strangers, 2. Bertalan, 3. Jakab, 4. Balázsi, 5. Dávid, 6. Farkas, 7. Gergely, 8. Váradi-Pető families, 9. Guests, 10. Priests, 11. Bikfalvi-Farkas, 12. Second-rank families

The Székelys from Bukovina migrated from the Székelyföld in the 18th century to Bukovina and settled where they are now in the southeastern corner of Transdanubia in 1945 (cf. p. 51). From the middle of the 18th century they have kept track of the clans, a practice that has begun to fade only during the last decades. There was an order of prestige among the clans, primarily based on the conditions of property. {68.} Governing each clan there was a head, who represented the entire community. He played a leading role during the times of weddings and burials. Newborn babies were introduced to him, as were the new wives. When they slaughtered a pig, they sent him a sample. He represented the young before the law, he bought for them and in their stead horses and cows at the fair. At times he called together the leading members of the clan to discuss more important questions, to set right the conflicts and quarrels within the clan. The head of the clan also participated in the governing of the village, because he represented a larger unit. The most respected men, the judges, also came from among them.

Clan consciousness was first and foremost expressed in helping each other within the clan. Communal work was undertaken at time of house construction and large-scale harvesting. If one of the members was struck by a natural disaster, everyone tried to help to get him on his feet. They visited the sick, they followed the dead to the burial together, and they participated in weddings together. The clan also possessed special marks. Thus in the Csibi family the men wore a peacock feather in their hats, which they passed on to the younger generation only after they grew old. Blood feuds, alive even in this century, claimed many victims. The clan tried to retaliate for any offence against its members, in many cases attacking a member from the other clan who actually had nothing to do with the hurt suffered.

A differentiation according to clans on the basis of conditions of property was noted in the village Rákosd in Transylvania, distinguishing between new or old settlers. Here the separation of certain clans can be demonstrated by the way they settled. The more prominent, leading clans lived on the lower, more spacious, more fertile territory of the village, while the poorer ones who settled later chose a place for themselves on the upper part, where the soil was poorer and where, because of the proximity of the forest, they also suffered more damage from the wild beasts and from robbers. The clans also parcelled out among themselves the cemetery that lay around the church, and here too {69.} the order of settlement prevailed. Similarly, they kept the same strict order in the seating at church, since every clan could use only its own bench both on the side of the men and that of the women. They entered the church in this order, whilst strangers and guests occupied the seats designated for them. The young wife left the bench of her own clan and sat with her mother-in-law and her sisters-in-law.

While the concept of the clan is known throughout the entire linguistic territory, the had can be found in a relatively small area amongst the Palotses, in the Jászság, Kunság, Hajdúság, Bodrogköz and Nyírség. It binds the families too on the basis of paternal lineage, but it seems as if it was a smaller unit than the clan. In many cases it was mixed up with the concept of the extended family, or was even identified with it. More modern observation proves that it also embraces a shorter period of time, because it includes only the living and not the dead. Its size even among the living extends only to three or perhaps four generations. Thus in a village in the Bodrogköz, a man called Hegedűs, who moved in from the other side of the Tisza as a son-in-law together with his grown sons and grandsons, in about six decades became the founder of the Hegedűs troop. The had in this area, therefore, is a concept of such a kind that, according to circumstances, can always be updated with newer content.

However, the had can also be connected with certain military organizations of the Cumanians and Hajdús, which prevailed in their basic forms until the middle of the last century. The so-called hadas settlements (according to had) located in these areas point to this phenomenon. Here families related to each other settled in a certain part of the village or market town, and in many cases families bearing identical names and belonging to one band lived there in 4 to 20 separate houses. They farmed independently but helped each other in work and in any kind of difficulty. In the Jászság they use the had designation when the old folk live in the settlement and the young people farm out on the farmstead, although in this case we are talking about a large family which farms together but lives separately.

The kindred (rokonság) has a wider scope than the troop. It includes not only paternal but also maternal descent, and in some places artificial relations as well, but never the dead. The significance of kindred has grown especially during the last decades, as the clan has been pushed vigorously into the background. Generally, kindred is counted up to the third or second generation, but in most cases it ends with first cousins. This is the limit of which kindred invite each other to weddings, at which it is proper to go to burials, and at which families try to help each other if need arises.

| Family Organization | CONTENTS | Artificial Kindred, Neighbourhood |