| Baptism | CONTENTS | Wedding |

Children’s Games

Lészped, Moldavia

The bulk of children’s poetry forms part of children’s communal games. From the point of view of their substance, children’s games are related to dramatic customs, and this relationship finds expression in the dialogue form, as well as in the presence of dance and song and mimicry, although there are games in which the last has no role. The number of {606.} such games, considering their many variations, is so numerous that we can survey even the most important ones only with great difficulty. Games for groups can be summed up in the following way: “In one type of group game (with roles and/or changing roles, e.g. tag, ‘white lily’, blind man’s bluff, ring games, etc.), the group itself remains basically unchanged, except that one child playing a certain role is then replaced, handing the brief role over to another, which mostly lasts until the song is sung. One child steps into the place of the other when the predecessor designates his successor. This change that hands over a role is the chief distinguishing sign of this type of game. The games in which couples are exchanged (ex: pillow dance) are the more adult versions of the former games, and they are closer to folk customs. And games containing competitive changing are the reversed versions of this type; these games allow the right of choice to the group.

Great Plain. 1930s

Debrecen. 1930s

Decreasing-increasing games constitute another large category of group games. These differ from all previous ones in having the group itself change: the circle becomes a disbanded (counted-out) group, the inward-turning circle becomes an outward turning circle, the standing circle becomes a chain that goes around (‘bride-asking games’, e.g. ‘walking around the castle’, line games), a bridge is built from a moving chain (bridge games and their relatives), a bunch of children are caught from a freely grazing ‘herd’ (goose games and their relatives). Certain selected players (if there are such) function only to effect orderly transitions: they call out the counting-out verse, designate the next child for turning out of the ring, or to lead the walk around the ‘castle’, etc. They take care that the movement from one to the other should connect them smoothly.

Vásárosnamény, former Bereg County. 1930s

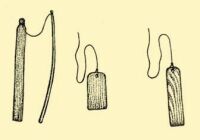

The game of forfeits is a substituting increasing-decreasing game. The child next in turn who makes a mistake pays a forfeit, which represents him.

The playing group arrives to the end of its career–to the border of its adult life–in the last group of games. Here the society of children, who used to change roles, now belongs into a community which dances and plays in a unified unchanging group (somewhat theatrical); neither change nor increasing-decreasing disrupts their community (Cf. György Kerényi).

Poroszló, Heves County. 1930s

Budapest, Ethnographical Museum

Szentistván, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Nógrád County

Szigetköz, on the Danube. Early 20th century

This division organizes our children’s games only from a formal viewpoint. However, it allows a good glimpse into the rich and colourful world of games. The investigator of folk poetry is primarily interested in the text of children’s games. The most varied types of folk poetry can be found in these texts. Lajos Kálmány aptly says that {609.} children’s poetry is a “virtual repository, a virtual asylum of folk poetry... There are in them every branch of folk poetry and every activity that happens in life... from the simple rhymed lines and lullabies to survivals of ballads. The tree of folk poetry is a very labyrinthian tree: its branches reach across each other, but nowhere else do so many branches come together as here among children’s games, which is why I have called it a virtual repository; if the wind catches and breaks some branches of folk poetry, they lean left and right until they tumble onto this branch, the branch of children’s games, then they join onto it, and that is why it is a virtual asylum.”

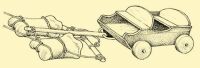

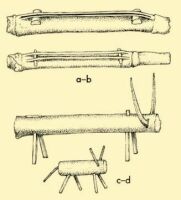

a–b) Fiddle. Gige, Somogy County. c–d) Ox. Galgamácsa, Pest County. Early 20th century

Indeed, a significant part of textual children’s games appear to preserve survivals of Hungarian folk poetry and constitute a priceless source for the historical researchers’of folklore. Nursery rhymes to scare away animals or to call them have preserved numerous historical memories. For example, one of the actors of a stork-scaring little poem is a Turkish child, and this undoubtedly preserves the memory of the centuries-long fight against the Turks, while one snail-calling verse speaks, in its various versions, of Turks and Mongols, and the threatening words of the text refer to their cruelty. We could continue to make a long list of such historical references. In the bridge games there is reference to “Our good King Lengyel László” and the fight of Hungarians and Germans. The memory of King Matthias survives in a game played with a ball. We can recognize in other children’s games the custom of recruiting soldiers. And the figures of the cruel oppressors of the people, landlords, wily judges, and pandours, also live in games.

Galgamácsa, Pest County

Szék, former Kolozs County

{611.} However, not only the memory of historical characters and events can be discovered in children’s poetry but also remnants of numerous old customs as well. The reason for this is that children naturally imitate adults. In certain animal-imitating games (goose game, goat game, etc.), research has discovered the late descendants of ancient animal descriptions, while other games have preserved in their songs and dances wedding customs that are in the process of disappearing.

Beside far-reaching historical roots of children’s games, we must also remember that these games exist in the present life of children, and the long survival of their motifs, which themselves can be traced far back into the past, can be explained only by their continual expansion with newer and newer elements, the creation of newer versions by children. These games have followed the transformations of social history, which influenced even the world of children. At times only a formula has been changed; at other times entire games have been transformed or have gained a new role.

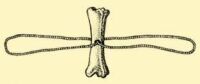

Historical survivals, however, represent only the most interesting elements of children’s games, but scarcely the most important. What is significant is that children’s games, precisely because of the aforementioned inclination of the child to imitate, observe the events of real life. Even little short poems are full of references to nature and to the animal kingdom, and the realistic images of everyday work are also to be found in them. “We crack salt, we crack pepper, we ring with a gourd” reads one sun-calling verse, and there are hardly any children’s games that do not refer to the most varied manifestations of farm work (guarding the animals, taking them to pasture, hoeing, spinning and weaving, sowing, harvesting, cooking and baking, etc.), not only in the text but also in the gestures that accompany the game.

Barskapronca, former Bars County. Late 19th century

After the age of twelve, children were counted less and less as children, but the young lads and girls did not yet admit them into their company. This mostly came about at the age of 16 to 18, and for boys, initiation took place usually in the tavern. The young man to be initiated invited the older ones, and while drinking they accepted him into their community. At such times one older lad adopted the boy like a godfather with the following words: “I have held you to be my good friend until now, but now I hold you as my good godson. At every step, if someone insults you, I will take care of you” (Garam Valley). Then the young man, thus initiated, could go to the tavern, to the spinnery, to dances, to girls’ houses; he could ask any girl to dance, and if someone attacked him the others hurried to his aid. Each year they elected anew the leader of the young men, the legénybíró (leader of the lads); the landlord and the leaders of the village also had a voice in this act, since they paid for his wine, while he was helped by the young men with his daily work. In some places the election was held at Whitsuntide, when he who defeated the others in horse-racing, or wrestling or bull wrestling, thus proved his suitability.

The organization of young girls was not as precisely regulated as that of the young men. In general, after her fourteenth birthday, a girl invited the older girls for dinner, who then accepted her among them. Although older records mention the election of the “queen of Whitsuntide”, who {612.} afterwards became the leader of the girl’s group for a year. This custom later was transformed into a children’s game.

The grown girls and young men did not use the familiar form of address towards each other. They met at work, on Sunday afternoon walks, in the spinnery and dance houses. Young men could go to the house of a girl only on definite days, generally on Saturday. If a young man and a girl had already come to an understanding, and if the parents did not see any obstacles to the marriage, then the boy visited the house more often. The girl could stay out longer when she saw him out, and among the Palotses they could even stay together in the sleeping room. At such times other young men would drop away.

| Baptism | CONTENTS | Wedding |