| Burial | CONTENTS | Customs not Tied to the Calendar Year |

Customs of the Calendar Year

The calendar customs are grouped around the spring equinox and the winter and summer solstices, but in order to survey them more easily we will introduce them in chronological order. The number and variety of these customs, interwoven and coloured with dramatic elements, is extremely varied by regions and ethnic groups, which is precisely why we venture to introduce only the most general, the most beautiful, that is to say, the most archaic forms.

It is very difficult to distinguish those customs which belong to New Year’s Day. The reason is to be found in the fact that up to the 16th century the New Year was counted from Christmas. Therefore, in many cases the customs cannot precisely be fixed in relation to a certain day. In the Middle Ages the serfs and servants visited their landlord and took him gifts. Perhaps as a direct continuation of this, herdsmen, servants, and also children used to visit the houses of more prosperous {638.} farmers on New Year’s morning and wish happiness for the following year with verse and song:

| May God give us everything |

| In the year to follow: |

| May the white bread swell up in |

| Hutches made of willow; |

| Wine, wheat and sausage |

| None of us need borrow; |

| Let us all forget all medicine |

| In the year to follow. |

Orosháza (Békés County) |

Children and young men made a great noise with cowbells, bells, and bits of iron to scare away evil from the house, its inhabitants and the stock. In part of the Székelyland we know of “burying” the winter, in which young men buried a straw doll representing winter. Around Lake Balaton they chased a hunchback through the streets and beat him with switches; they called this the “expulsion of winter”.

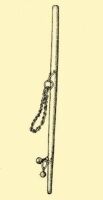

Many customs of mainly religious content are attached to Epiphany, January 6 (Vízkereszt), since this is the twelfth and concluding day of Christmas. The custom of the Three Magi (Háromkirályok) shows much similarity with Christmas carolling, although it makes less use of dialogue form. Its most important props is the star, which shows the way to Bethlehem for the Three Magi. In a letter from Somogy County this is mentioned as early as 1540: “Then send on the star songs, if you have them; try all the more to find other songs if you can because I have a good child here, whom I will send on to you if I cannot protect him [e.g. from the Turks].” The star is carried by one of the Three Magi, dressed in white, on a pole or on an expandable and contractable sectional implement, used for this purpose. They smear soot on the face of Balthazar, to indicate his being a Saracen. They go from house to house and enter with this song:

| Eastern wise men three went on a journey, |

| The star is a-twinkling! |

| Now it is standing over the stable, |

| The star is a-twinkling! |

| Eastern wise men three went on a journey, |

| The star is a-twinkling! |

| Kings they are saying good day to the Virgin, |

| The star is a-twinkling! |

| Kings they are bowing heads to the Maiden, |

| The star is a-twinkling! |

(Veszprém County) |

After each of the three has said his verse, they get food and money from the master of the house.

Szakmár, Bács-Kiskun County

In many regions even today the clergyman and the cantor, with a few altar boys, go through the village and consecrate the houses. They write the year on the door and under it the initials of the Three Wise Men: GMB. At such times the faithful give food and money, which the {640.} children collect in baskets and bags. This custom was mentioned in 1783: “On the day of Epiphany the clergy go to every house with a cross and prayers and together they ask for alms (kolendálnak),” that is, they collected gifts. The term kolendálni is used even when just children go alone and collect gifts for themselves.

The custom of celebrating St. Blaise (Balázs, called Balázsolás, on February 3), is known primarily in the western half of the Hungarian linguistic region. St. Blaise is the patron saint of children, he is not only a teacher but also protected children from sickness. A Balázsoló group consisted of several members. In Zala, at the beginning of the century their names were recorded in this way: warrior (vitéz), general (generális), bishop (püspök), corporal (káplár), standard bearer (zászlótartó), sergeant (strázsamester), keeper of the bacon (szalonnás), alphabetizer (ábécés). The many military ranks can be explained by the children’s entering the houses under the pretext of recruiting for school:

| ’Tis today Saint Blaise’s Day; |

| Long it’s been a folkway, |

| Ancient custom, |

| That this day the schoolkids |

| All their fellows, pals with |

| Go recruiting. |

| Taught by our teachers |

| How to be good creatures |

| Came we hither: |

| Every sluggard, wagger, |

| Every truant, slacker |

| For to gather. |

| Is there in this house then |

| Any of such children? |

| If so, hurry, |

| Join our little group, too, |

| Come away to school, you |

| Won’t be sorry! |

However, the purpose of the custom was collecting, as was often indicated also by the naming of some participants: Satchel Carrier (Tarisznyás), Skewer (Nyársas), Basket Carrier (Kosaras), Keeper of the Bacon (Szalonnás). In return for the alms, they asked that the sore throat (diphteria) should not take its victims from among the little ones.

In its history, the custom of celebrating St. Gregory’s Day (Gergelyjárás, March 12), appears to be older than the Balázsolás, but similarly, it is a custom of students. Greetings for St. Gregory’s (Gergely) Day have been passed down to us from as early as the 17th century, one of the most beautiful versions of which is preserved by Csángó folk poetry. The two stanzas below are from there and, like the entire poem, they evoke medieval traditions:

| Doctor St. Gregory, |

| Holy of memory, |

| On this thine day, |

| Heeding old tradition |

| And the Lord’s provision |

| Go to school we. |

| Lo, the little birds too |

| Multiply in number |

| For to grow up later; |

| Now the spring is come in, |

| Day and night are singing |

| Very sweetly. |

Students who collected alms for their school in the Middle Ages, and later their Protestant successors, certainly played a significant role in making the customs of Balázsolás and Gergelyjárás known. These late successors are the mendicants, who even a few decades ago went around the villages on large holidays and collected for Protestant schools.

Carnival (farsang) starts with Epiphany and lasts until Ash Wednesday, but is especially festive from the Sunday before Ash Wednesday until Tuesday evening, which is generally called the “tail of Farsang”. This is one of the joyful holidays of spring, which had overcome winter, cold, and darkness. Medieval sources already recall it. Most certainly the custom came to the Hungarians from the West, as is shown by its Austrian–Bavarian name, which appeared in the form of a family name as early as the 14th century. The churches always persecuted carnival and its most varied manifestations, as is demonstrated by a notation originating from 1757: “The Hungarians took over that famous Farsang from the Germans, who formed it from the deeds of cantu circulatorum, pursuer of playful jokes and dirt; who initiated many kinds of games and foolishness on this day, and at this time entertain guests and rush around having a good time.”

At the end of Carnival the names of those girls who had not succeeded in getting married were shouted out. The young men, amidst a great deal of noise, recited different songs and rhymes in front of the houses where such girls lived:

Moha, Fejér County

In the western part of the linguistic region, the custom of stump dragging (tuskóhúzás) falls at the end of Carnival, a mocking ceremony organized by the young men. An 1820 description says as follows: “In the past, on Ash Wednesday, in Hungary, those marriageable girls who had not got married during the days of farsang were made to drag tree stumps like some unbroken mares.” In some parts of the Great Plain the young men raised a great clamour with pots and pieces of iron under the window of the girl and shouted the following:

| Pancake Day! Shrove Tuesday! |

| Some girls would now maidens stay. |

| Those who have a girl to wed, |

| Lead her to the herd instead. |

(former Szabolcs County) |

{643.} Alongside the great many mummeries of Carnival there also occur the customs of driving out evil and working magic on the crop. At such times they threaten the fruit trees with an axe that if they do not yield enough, they will cut them down.

At the northern edge of the linguistic region the kiszehajtás comes about at the end of winter and beginning of spring, generally on Palm Sunday. The word kisze originally means a typical Lenten food: sour fruit- or bran-soup, which people became very tired of through the winter and want to get rid of. The girls dress up a straw doll in the clothes of a young wife who was married in the previous year (this symbolizes the kisze) and carry it singing to the nearest river, stream, or lake. They take the clothes off the straw doll and throw the doll into the water. At this time they foretell the marriages, of those present from where and how the water carries the straw and doll. To this day some of the songs still recall the memory of getting free from Lent:

Moha, Fejér County

Moha, Fejér County

They ridiculed the young wife who had refused to give her clothes. They also believed that by taking the kisze out they put a stop to illness and fog. There are also data showing that at some places they burned the straw doll instead of throwing it in the water:

| Kisze burns, it burns anew, |

| Wisps of smoke a-twining; |

| Spring is near, the sky is blue, |

| Warm the sun is shining. |

| When its smoke does disappear, |

| Frosty fogs we need not fear: |

| Spring is come and stayeth here. |

(former Hont County) |

Szandaváralja, Nógrád County

Acsa, Pest County

One important area within the spring circle of celebrations is Easter. Easter Monday sprinkling is general in the whole country, and in the past used to be done at a well with buckets (cf. Plate LIII). If the girls did not come by themselves, then the young men dragged them there by force. Basically, sprinkling with water is connected to fertility rites. Later sprinklers began to use perfumed water, but received coloured and decorated eggs (cf. p. 420) just as before. This custom is still flourishing today. Sprinkling poems spread and differ according to time and region.

The Easter egg, one of the most general symbols of fertility, has significance even on the so-called White Sunday that follows Easter. This is the time when godparents send a so-called “koma platter” to their grandchildren, and the smaller girls present them to those to whom they want to show their respect, and want for a friend. This custom survived longest in Transdanubia and the Palots region. Thus in Somogy they put a bottle of wine, a few red eggs, and pretzels on a plate, cover it with a white or colourful cloth, and carry it ceremoniously to the selected koma. The girl who hands it over recites the following little poem:

| Koma-plate I brought you, |

| I had it adorned, too. |

| Gossip sends it, relative, |

| Gossip should a present give. |

(Somogy County) |

In Gyöngyös and its surroundings the girls receive a koma platter from their lovers and the young men receive them from the girls. If they accept the koma platter, this means that sentiments are mutual.

Mezőkövesd

{647.} May Day has for long centuries been the joyous celebration of spring. One of its most beautiful features in European practice is putting up a Maypole.

Young men went out to the forest and selected a long-trunked, fine, leafy, branchy tree. This they put up in front of the window of a girl one of their mates was courting, and in this way he showed his intentions towards her. In some places the young men set up the tree while the girl and her mother provided its colourful decoration. When the tree began to wither, it was “danced out”, that is, young people organized a smaller dance at its felling. On this ancient day of celebration, since a very long time, city dwellers used to go out to the forests and amuse themselves until evening. After such antecedents, and beginning with 1890, May the First has become the holiday of workers in Hungary. The day is celebrated with a parade, with outings and picknicking.

The summer circle of calendar holidays begins with Whitsuntide, when the children go around greeting:

Another version of the custom of choosing a king and queen at Whitsuntide occurs among the games of little girls. A little girl–the “Queen of Whitsuntide”–is covered with a kerchief and the group of girls enter every house, raise the kerchief for a moment, and show the “Queen” with the following words:

| God has brought us Whitsun, |

| Pinky Pinkster Sunday. |

| All around we carry |

| Whitsun queen for one day. |

Gencsapáti (Vas County) |

Vitnyéd, Győr-Sopron County

{649.} Fertility rites are also connected to this custom in western Transdanubia; they lift a little girl up really high and shout, “May your hemp grow this high”. At Apáca, in Transylvania, “cock shooting” or “cock hitting” (kakasklövés) took place at Whitsuntide. The boys used to shoot arrows at a live cock, and later on at a target. The shooting lasted until they hit the heart, or the centre. Meanwhile humorous mourning songs were recited, and in the evening a cock supper was held.

Most significant among the customs of the summer is lighting the fire of Midsummer Night (szentiváni tűzgyújtás) on the day of St. John (June 24), when the sun follows the highest course, when the nights are the shortest and the days the longest. The practice of venerating St. John the Baptist developed in the Catholic church during the 5th century, and at this time they put his name and day on June 24. Naturally, the summer solstice was celebrated among most peoples, so the Magyars may have known it even before the Conquest. Although the Arab historian Ibn Rusta speaks of the Magyars’ fire worshipping, we so far have no data that could connect it to this day. At any rate, in the Middle Ages it was primarily an ecclesiastical festivity, but from the 16th century on the sources recall it as a folk custom. The most important episode of the custom is the lighting of the fire:

| Lay we fire, pile it, |

| Lay it out to square shape: |

| In one of its corners |

| Sitting are fine old men, |

| In the second corner |

| Sitting fine old women, |

| In the third again are |

| Sitting lusty laddies, |

| In the, fourth are sitting |

| Lovely maiden lassies. |

Kolony (former Nyitra County) |

The custom survived longest and in the most complete form in the north-western part of the linguistic region, where as late as the 1930s they still lit a Midsummer Night fire. The way of arranging the participants by age and by sex has suggested the possibility that these groups sang by answering each other, but there are hardly any remnants that appear to support this possibility. People jumped over the fire after they lit it. This practice is mentioned as early as the 16th century, although at that time in connection with a wedding; still, it is called “Midsummer Night fire”. The purpose of jumping over the fire is partly to purify, partly because they believed that those whose jump is very successful will get married during the following carnival:

Kazár, Nógrád County

Lighting and jumping over the Midsummer Night fire also had a definite match-making role, and can be compared with the customs and folk poetry of the winter solstice.

Customs relating to agriculture predominate among the customs of the autumn, and perhaps the extremely large amount of work to be done then is the reason for the much smaller number of other types of customs at this time.

One of the richest circles of celebrations are attached to Christmas (karácsony). The pagan world of tradition, itself related with older anniversaries, as well as the more recently developed peasant customs, both fused into the holiday circle of the ecclesiastical year. Religious customs and celebrations of the ecclesiastical year in their reality could not be understood without considering such an interlacement. We need not think that in all cases we are dealing with survivals of traditions from the pagan period, but it is certain that anniversaries so important for the peasantry, the customs, traditions, and beliefs of spring, summer, autumn and winter equinoxes or solstices, are connected with and have melted into the traditions of the ecclesiastical year. The church, faithful to its thousand-year-old and well-established methods, has outright consecrated some of these customs and installed them among the {651.} religious holidays, while it has quietly overlooked others, due to their important function in the life of the people. Thus we can observe in the holiday customs of the people, in their beliefs tied to the ecclesiastical year, the peaceful co-existence of the most varied strata. Ancient beliefs of the pagan period, more newly developed peasant superstitions, Germanic and Slavic influence–and accompanying these, customs that spread because of the influence of Christianity as well as certain elements of the religious concepts of antiquity–all of these can be found in the folk customs and celebrations that are attached to the holidays of the ecclesiastical year. The best example of this is the holiday cycle of Christmas.

Christmas celebrations really begin with Advent, the first day of which is the Sunday that falls closest to St. Andrew’s Day (November 30). In some places they signalled its beginning by ringing the bells at midnight, and from then on all loud musical entertainment was prohibited. The girls and women went to church in black, or at least in dark-coloured dresses.

The celebrating of Saint Nicholas’ Day (December 6) is one of our newer folk customs. Thus the giving of gifts to children began to spread in the Hungarian villages only in the last century. The Hungarian peasantry also took over mummery (alakoskodás) from the West, but that seems to be older than gift giving. Thus in Csepreg in 1785 they were already prohibiting this custom: “And because it has been experienced from ancient times that some among the citizens, on the evening or during the night before the day of Bishop Saint Nicholas, go from house to house in various garbs and frighten the young children with scary, ugly figures, contrary to common sense, it is strictly ordered that nobody among the citizens shall dare to permit their children or their servants to go around in such colourful garbs on the night before Saint Nicholas’ Day.”

Before the Gregorian calendar reform, St. Lucy’s Day, December 13 (Luca-nap) was the shortest day of the year, which is why in many places until quite recently the Hungarian peasants counted the lengthening of the days from here. The women did not work on this day. The men began to make the “Lucy chair” (Luca szék), carving a separate piece one day at a time from different kinds of wood, so that the chair would be finished exactly by the time of the Christmas Eve Mass. He who sat on it during Midnight Mass would see the big-horned witches in the church, but then he had to run homeward immediately because if they recognized him he would have been torn apart by them. (Géza Róheim wrote one of his first large-scale monographs about the beliefs of Lucy’s Day, the historical precedents for the making of the Lucy chair, its international connections, and its ethno-psychological meaning.) In Transdanubia, children go from house to house on this day and charm the hens with ditties so that they will lay eggs all the year around. They wish everything good to the people of the house with a poem:

A custom called “looking for lodgings” (szálláskeresés) is a recent religious custom. Nine families got together and from December 15 on carried the picture of the Holy Family to a different house every day, singing and praying in front of it. Then they gave gifts to a poorer family, as if they were giving them to the Holy Family.

Szakmár, Bács-Kiskun County

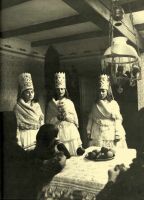

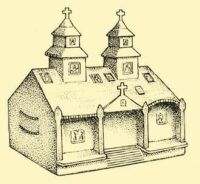

The most popular Christmas custom is the Nativity play (Betlehemezés), which was known in the near past throughout the entire Hungarian linguistic region and was played even in cities. Records speak of mystery plays in the church as early as the 11th century, but later these were ousted from the churches and in the 17th to 18th centuries were {653.} performed in schools and by religious societies. It seems that the custom became general only in the last century, at least in the form and by the name known currently (cf. Plates LIV, LV).

Generally 16 to 18-year-old boys played in the Nativity play, girls doing so only among the Matyós (cf. p. 43), where the Nativity in the shape of a church was carried by an older woman. A runner (kengyelfutó) from among the players went ahead of the rest, who in Torda of Transylvania asks for admission with verses like this:

| Praised be the Lord Our Jesus Christ! |

| Holy day, the brightest feast day |

| Breaks for Christians with this morning, |

| Though the Holy Church of Nature |

| Clad she is in silent mourning. |

| Long ago in Bethlehem town |

| Shepherds sang about the Saviour, |

| Who descended and redeemed us |

| And has always helped poor people. |

| Honoured Host and meekly masters! |

| Outside are my friends awaiting; |

| What, my good man, is thine answer: |

| Wilt thou let my friends advance here? |

On an affirmative answer the participants come in. Two “angels” bring in the church-shaped Nativity, and they are followed by King Herod, Joseph the father, and two or three shepherds who lie down in front of the Nativity. Only when everybody has settled down do they start to pretend awakening and begin songs the content of which varies by regions:

| Rise, shepherds, rise up, men, |

| Go we quick to Bethlehem! |

| Haste as we are able |

| To a ragged stable! |

| Start we now, e’en tonight, |

| So we get there still before the morning light, |

| And we pay our Lord respect as best we might. |

| Oh he’s cold, the poor thing, |

| How his tears are pouring! |

| Pillows soft prop not his head, |

| Nor he lies on feather bed |

| But in hay and straw instead, |

| For a stove to keep him warm there all he hath |

| Is from cows’ and donkeys’ mouth the steaming breath. |

Pásztó (Heves County) |

Usually after such an introduction comes the brief description of the birth of Christ, then Joseph tells how he tried without success to find lodging, and then the shepherds render homage in front of the infant Jesus. A comedy follows, the humorous rivalry and squabble of the shepherds, and after the performers have been treated to food and drink, the players sing their blessing together:

| {654.} Hurry, goodman, if you would, |

| Give us speed for go we should. |

| May God give you every good, |

| You, your house and neighbourhood. |

Tiszakarád (former Zemplén County) |

Lengyeltóti, Somogy County. Early 20th century

Numerous other variations have also been recorded, especially if we take in consideration the puppet Nativity plays (bábtáncoltató betlehem), the most complete form of which were recorded in the north-eastern and western parts of the linguistic territory. The Szatmárcseke version has seven different puppets: two old shepherds, two shepherd boys, two angels, King Herod, the Devil, Death, Small Mike, and the one who collects the candle money (gyertyapénzszedő). The sequence of the play and the songs are similar to those in other Nativity plays, but here a single child moves the puppets on the church-like, towered stage, made especially for this purpose. As a conclusion, the candle-money collector puppet comes on stage and recites the following verse:

| Here this box of copper, |

| Hungry pot of money, |

| Waits for you to drop a |

| Penny as is proper. |

| Make it all the richer, |

| For today was born little Jesus. |

Szatmárcseke (former Szatmár County) |

Lengyeltóti, Somogy County. Early 20th century

Nativity players began to prepare their equipment at Advent, when they learned the poems and songs, and they went about in the village often for ten days, certain groups of them even going to neighbouring settlements.

Jákfa, Vas County. First half of 20th century

One of the oldest Hungarian customs, the regelés or regölés (minstrelsy) (cf. p. 36), is connected with the second day of Christmas, Saint Stephen’s Day. According to philological findings the word reg may have meant an occasion of royal and lordly entertainment in the Middle Ages, during which the regös men (minstrels) entertained their lords. The word itself is connected to the shamanistic word révülés (entrancement), so that it can be supposed that at least in part it is traceable to pre-Conquest times, while on the other side it has links with the different types of European mummers’ plays. The main role of the songs, melodies, and jokes of medieval minstrels was entertainment, but they often included social wrongs that the country or the leaders of certain large regions would otherwise not have heard about.

However, the custom of minstrelsy associated with a certain time of year must also have been known among the people. In a note from 1552 referring to Transylvania, we can read: “After the birthday of our Lord Jesus Christ comes the big celebration of the Devil, the week of minstrelsy... There is no end to the plentiful drinking and abundant song.”

Kéty, Tolna County

Alsóhahót, Zala County. Early 20th century

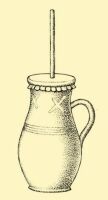

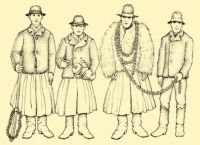

In the last century the custom of minstrelsy was practised in almost two hundred villages of Transdanubia, especially in its western part, as well as in certain parts of the Székelyland. Children and young men {656.} went around the village mostly dressed in pelts. They rattled their scary-sounding chained cudgels and tried to make as much noise as possible with their jug pipe–which is nothing other than an earthenware jug covered with a membrane–and in many other ways. They went from house to house and entered with such greetings as the following: “We, the servants of Saint Stephen, have arrived from a cold and snowy country, our ears and feet are frozen, and we want to cure them with your gifts. Shall we tell it or press it?” If they got permission from the farmer to tell their story, they started on the song full of character and implying mythical, archaic connections. One of its parts, coming just after the introduction, are words wishing the magic of plenty, wishing every kind of good, heaped up to overflowing, to all the people in the house. (The ancient refrain in this and the following song have since become obscure in meaning):

Region of Göcsej, Zala County. 1930s

In the second part comes the turn of those girls and young men who are going to be paired off or “minstreled” together. It is believed that those whose turn comes in this way will get married after the next Carnival:

| Here we know a lassie |

| By the name of Julcsa; |

| There we know a laddie |

| By the name of Pista. |

| May God not defend him, |

| In his bosom tend him! |

| Chase him from the garden, |

| Let him have no pardon, |

| Choke him in a pillow |

| Make him cry and bellow |

| Like a sow her farrow, |

| But a little still more so! |

| Haj, regő, rejtő! |

| This too grant He might thee, |

| God our Lord Almighty! |

Miháld (Somogy County) |

A mummer disguised as a bull usually runs in after the song and keeps frightening the children and girls, after which the minstrels ask for a reward for their song. One of the earliest recorded versions from Transdanubia even tells about this:

| Goodman is abed a-lying, |

| Tied around his waist his wallet; |

| In it are two hundred forints, |

| Half belongs to regös minstrels, |

| Half goes to its owner. |

| Gowns we have of buckwheat stalks, |

| Shoes we have of oak-tree bark. |

| If you let us out now, |

| Off we go a-skating! |

Various versions often mention the oak- or birch-bark sandal (bocskor), and the minstrels usually call themselves the servants of Saint Stephen. Undoubtedly all of this refers to great antiquity. Besides the young men, married men also indulge in minstrelsy in the Székelyland, but they formed a group of their own. They generally sang a verse at the house of young married couples rather than at those of girls, and to this verse is attached the De hó reme róma refrain, the content of which is not quite clear.

The Transylvanian version also differs in talking about the “red ox” rather than the stag, so that this is some custom of mummery in which at one time the bull, the ox, stood at the centre. Hungarian ethnology has occupied itself considerably with the customs and poems of minstrelsy, but in this regard it has not yet been able to arrive at a confident, final solution.

Holy Innocents’ Day whipping (December 28) belongs among the old customs of ecclesiastical origin, although in the final count we can follow its trail back to antiquity. They beat the children with switches in memory of King Herod’s killing of the infants. The following was written in an 18th century notation from Transylvania: “On this day the fathers or others hit the little children with switches early in the morning, in memory of the suffering of the infants for Christ, and because they too shall have to suffer in this worldly life.” But the switch was also used on those they wanted to urge to do more diligent work. People also tried to get rid of sickness and boils with their ditties, among others, this one:

| Do as told and be good, |

| If they send you upward, down you go, |

| If they send you downward, up you go, |

| If to fetch some water, wine you bring, |

| If they send some wine for, water bring, |

| Be you hale and hearty, lively, never have no sores! |

Zalaistvánd (Zala County) |

We have mentioned only the most important among the calendar customs of the year, but the celebration of Name’s Day also belong here and is practiced throughout the country. Among these the most important are precisely those attached to Christmas: St. Stephen’s day and {659.} St. John’s day. At this time the children go from house to house, recite their verses, and expect gifts. Many of the verses are of half-folk origin, having been written by cantors, but there can also be found among them some really beautiful ones:

| Up and get, good men meek, for the dawn’s breaking there, |

| Angel-like hovers on wings of gold, bright and fair. |

| Every flower will deck itself as it blows |

| And it will dry itself on a soft lily-rose. |

| As many grass-blades do grow in the motley mead, |

| As many water drops lie in the ocean bed, |

| So many blessings shall fall on St. Johnny’s head! |

| All of us wish him well! |

Nagyszalonta (former Bihar County) |

| Burial | CONTENTS | Customs not Tied to the Calendar Year |