| The World of Hungarian Folk Beliefs | CONTENTS | The Peasant World View |

Figures of the World of Beliefs

First among the figures of the world of beliefs of the Hungarian peasantry, we will mention the táltos, as one in whom the features of the pre-Conquest shamanistic faith can be found most prominently. The word táltos itself is presumably Finno-Ugric in origin, and its Finnish equivalent means “learned”, which is just what regional dialects of Hungarian call people endowed with supernatural powers. Today, the characteristics and equipment of the táltos can be analyzed mostly from the legends of belief (cf. p. 675) that still live in the memory of old people living primarily in the eastern half of the country.

{671.} The táltos is generally supposed to be well-meaning rather than punitive. He does not gain his knowledge by his own will, but receives it, as one of them bore witness during the course of an interrogation in 1725: “Nobody taught me to be a táltos, because a táltos is formed so by God in the womb of his mother.” Therefore no matter how much his parents and relatives might oppose it, he who has been ordered to his fate must carry it through.

A child was carefully examined at birth to see if he had any teeth or perhaps a sixth finger on one of his hands. One extra bone already foretold that with time the child would become a táltos. However, to become one, it was also necessary that the ancestors steal him for three or more days. One accused said, when interrogated for charlatanry in 1720: “... lying dead for nine days, he had been carried off to the other world, to God, but he returned because God sent him to cure and to heal.” They called this state elrejtezés, being in hiding, which is also a word of Finno-Ugric origin, and we can find its equivalent both in form and content among the related and various peoples of Siberia.

They maintain that while the táltos-designate is asleep, the others cut him to pieces to see if he has the extra bone. This motif also occurs in the Hungarian version of the generally known tale, “The Magician and his Apprentice” (AaTh 325): the kidnapped youth is cut up, usually put together on the third day, and by this gains for himself a previously unknown knowledge.

However, the táltos-designate’s struggle and trial is not over then, because he has to take a test. One way of doing this is by climbing up a tree that reaches to the sky, and if he returns without trouble, he can practise his newly acquired knowledge.

Tradition also tells about the equipment of the táltos. Among these we shall mention various headdresses: the feather duster and the horns. In most cases it is possible to ascertain that the horns resemble the horns of cattle, but less frequently stag horns also occur. Memory of the shaman drum also lives vividly, often paired off with a sieve, which occurs even in children’s verses (cf. p. 610) and Midsummer Night songs:

| May God give us gentle rainfall, |

| May He wash them both in one, all; |

| Sift in sieve on Friday, |

| Loving be on Thursday, |

| Drum Wednesday. |

Sárrétudvari, former Bihar County. Second half of 19th century

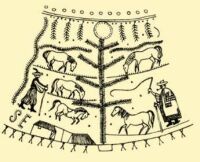

The magical mummers of the Hungarians of Moldavia go about on New Year’s Day with a sieve, on the side of which they fasten rattles and bells. At one time the táltos used this for curing sicknesses, for divining, and for conjuring up abundance, just as did the shamans of Siberia. The Táltos Tree, already mentioned at the time of the pagan revolts (11th century), was known nearly up to the present. As late as the beginning of the past century, they wrote the following about a táltos of the Sárrét: “He goes down, he knows where, and by climbing up the big tree, he will find out what a bad man the village magistrate is. And he can cause what he wants to happen to the village magistrate and to the village.” Thus the tree, usually depicted in folk art with a little bird sitting on top, {672.} was at once one of the táltos’s instruments and the symbol of his power.

with the Tree of Life, the sun and the moon.

Biharnagybajom, former Bihar County. Late 19th century

Among the activities of the táltos we must especially emphasize ecstasy, which the Hungarian language calls rejtezés (hiding) and révülés (ecstasy). Both words in their foundations can be traced back to the Finno-Ugric period, and it can be ascertained that they were related to shamanistic rites. However, we know that the religio-psychological meaning of ecstasy was not part of the shaman religious world view alone, for it was also known among the archaic beliefs in ancient religious traditions. The táltos, the learned one, can create contact with supernatural beings and with the spirits of the dead ancestors only in the state of ecstasy.

The other activity known from stories of belief (cf. p. 589) throughout the entire Hungarian linguistic region is the táltos combat (táltosviaskodás). The táltos from time to time had to fight the táltoses of the neighbouring areas in the shape of a bull, stallion, or perhaps a fiery wheel, just as described in a lawsuit of the Great Plain about a village boundary in 1620: “... The táltos of Békés fought the táltos of Doboz, but the táltos of Doboz was a match for the táltos of Békés.” The strange bull usually came down from a cloud and brought along a storm, while the people were able to help the local bull.

We have reason to suspect that remnants of a one-time táltos song survive in the “haj, regő rejtem” line of the minstrel songs (cf. p. 657), which supposedly means “I conjure with magic”, or in these words even closer to shamanism, “révüléssel révülök” (“I am ecstatic in a trance”). Indeed, the language of our nearest linguistic kindred, the Ob-Ugrians, the name of the shaman song developed from the kai, kei word, which is the exact etymological equivalent of our haj, hej interjection, and the name of the Hungarian shaman song may have been hajgatás.

The recently deceased Vilmos Diószegi, who made a great contribution to the field of táltos and shaman research, observed as the summary of his investigation: “The selection of the táltos-designate by illness, lengthy sleep, as well as by the cutting up of his body, that is, his gaining knowledge by way of finding the ‘extra number’ of bones in his body, his initiation by climbing the tree reaching to the sky–all this projected, even in its details and also in its entirety, the images formed by the Magyars of the Conquest of the táltos-designate. The single-bottomed drum with rattles on it in the hand of the táltos, which also serves as his saddled animal, as well as his owl-feathered or horned headgear, his notched or ladder-shaped ‘tree’ with the sun and moon on it disclose the equipment of the táltos of the Magyars of the Conquest, and his ecstasy, the combat that followed it, his conjuring of ghosts with interjections also reveal his activities.” Therefore the táltos figure of the world of Hungarian folk beliefs even today is closely attached to the shamanism of Eastern Europe and Asia.

The figure of the garabonciás was strongly mixed during the centuries with that of the táltos, but this figure originates from the West. The name itself is perhaps connected with the Italian word gramanzia, “enchantment, devilry”. He is equally supposed to be ready to do good or evil, to conjure up storms, and he reads enchantments from his book because, {673.} strictly speaking, he is a version of the medieval journeying student who had finished the seven or thirteen years of schooling at the university. In the course of this he had also acquired black magic, which he passed on to the peasants during his wanderings. The Wandering Scholar knocked on the doors of the peasant houses and asked for milk or eggs to eat. If they refused his request or gave sparingly, he conjured up a storm and sent hail to the fields of the entire village, while he rode away on the back of a dragon. His figure appears to be more revengeful and dangerous than that of the táltos and undoubtedly, in the world of beliefs of the Hungarian peasantry, he represents European black magic.

Boszorkány (witch) is a word of ancient Turkish origin, in the vernacular meaning a woman, although in the minds of the people either a man or woman can be a witch. In many areas witches are called bába or vasorrú bába (iron-nosed witch). The word bába is a Slavic derivative where the meaning “old woman, witch” can equally be found. As the names differ, so too the features which characterize Hungarian witches originate from several layers. Many different kinds of practice, procedure, and what the Hungarian language collectively calls babona (superstition) cling to this figure. The word babona is also Slavic in origin, perhaps taken over by the Magyars from some ancient Russian dialect, since numerous elements within this circle of belief can be found that indicate pre-Conquest Eastern Slavic contact.

According to Hungarian folk belief, the acquiring of a witch’s knowledge is generally an active step (cf. p. 591). Most frequently it was learned at midnight at crossroads, where the person would draw a circle around herself with a stick, which he or she was forbidden to move out of or even if a four-horse carnage or a bull charged or if a millstone on a thread was rolled over him or her. If the seeker of witchcraft could overcome her fear, she then could become a witch. At other times, the meat of a black cat was consumed for the same reason, or skill was acquired in the cemetery at midnight, but it could also happen that a person climbed a tree or a dry stalk of a weed, just like a táltos, and came back from there with the acquired knowledge. Witchcraft was most often transmitted within the family. It was passed on to the younger generation on the deathbed with a handshake. But no matter how it happened, the designate had to do something to get the power, while at the same time a chance to refuse it also existed.

However, once the witch had acquired her knowledge, she then could not put it down, because her colleagues would not leave her in peace and she became unlucky all her life. They believed that a witch is punished for her sins after death; she goes to hell, where snakes and frogs rip apart her guilty soul.

A wave of witch-persecutions passed through all of Europe in the 16th to 18th centuries, and these, in a somewhat weakened form, also reached Hungary. We first hear of them in more detail from the second half of the 16th century: “I could also tell a lot about women getting around at night, jumping in the form of cats and going among themselves like many gallants, ravers, dancers, drunkards, lechers, who with a half foot push little children into the sea, who cause damage and much mischief, and among whom many were burned, not long ago, around Pozsony, {674.} in the year 1574, after having testified to their terrible deeds. They also have a queen, and on her word the devil does horrible things.”

Witches were regarded with caution mixed with a certain fear, so that at times even the tithe collectors avoided their houses. Although witch trials were fairly frequent in Hungary, large scale witch burnings like those in the West were rare. Nevertheless, in Szeged in 1728 nine women believed to be witches and in Debrecen a decade later three others met their death by burning at the stake.

Witches were supposed to have formed certain organizations, which differed from region to region. The leaders were generally men, as in 1722 in Békés County: “András Harangöntő was a very famous master witch who not only practised healing, cast spells, and practised enchantment, but was also the head, the master of that army of witches that, according to him, formed and organized a collective within the area of our county.” In such organizations captain, lieutenant, flag-bearer, corporal, and scribe are mentioned. The organization, as in the case of western, primarily German witches, imitated the army. It has also come to light from the data that, from the middle of the 17th century, a strong German influence showed up in Hungarian belief about witchcraft, elements of which survived almost to this day.

However, contrary to this, shamanistic features were undoubtedly preserved also, a few of which are worth mentioning. Thus witches had “horns”, which could be seen by a knowledgeable man who sat on the Lucy Chair at Christmas during the Midnight Mass. Documents from witch trials also mention the drum among the equipment of a witch. According to an 18th century confession from Szeged: “... a stout beggar woman at Felsőváros has the copper drum, because she wants to teach her son, who is 18 years old. She wants to enlist him into the order of captains Dániel Rósa and Ferenc Borbola. The stout beggar is such a witch, because the plaintiff is old and cannot carry the drum, which is why they ordered it. Like a pint pot, it was that big.” It is presumably not because of the weight of the drum but because of the exhausting nature for body and soul of the ecstasy that they wanted to initiate the young man into the knowledge. We know from Bodrogköz that witches were supposed to take the bones out of sleeping people, which brings to mind the search for the extra bone of the táltos. That is to say, the witches wanted to acquire knowledge through possession of these bones.

Witches gathered together regularly to carouse and dance on one of the hills or islands, or at the edge of the forest. Therefore there is hardly a settlement in Hungary where a certain geographic name does not preserve this practice. Even so, the Gellért Hill in the middle of Budapest, rising on the bank of the Danube, was the most famous and central place for such gatherings in the whole country. It should be noted that according to tradition the pagan Magyars, who did not want to be converted, rolled or, more correctly, threw Bishop Gellért, nailed up in a barrel, into the Danube from the top of Gellért Hill. Stories of the witches’ visit to Gellért Hill and their flights of many hundreds of kilometres from there have also survived. Thus in Kassa, in a collection of sermons published in 1794, a preacher chastises the faithful in this {675.} way: “They say that witches and he-devils saddle people and ride to Saint Gellért Hill, or to where, they alone know, that with a mere look they stop empty carts so that that cannot move an inch, that they can bewitch cow, calf, and small children in thousands and thousands of different ways merely by the spell of eyes or look. But you know better than I what else is believed about witches and what is not.” Research during the near past has also disclosed the belief that witches gather at the Gellért Hill from within a 200–300 kilometre radius, flying there even from as far as Székelyland.

A witch carried out her bewitching usually not in her own form but after she had changed into some kind of an animal. Most often she appeared in the form of a cat. Then, primarily on the night of St. George’s Day (April 24), she would try to take the milk yield of the stock. As a precaution, the farmers would put some kind of spiky object, usually a harrow, in the door while they themselves kept watch with a pitchfork so that no cat could sneak into the barn. Witches are also believed to take on the shape of a goose, duck, hen, brooding hen, and chicken, as well as the shape of a dog and horse. Interestingly the cow does not appear among these domestic animals, only its horn, imagined as an attribution, the witch herself maintaining her human body. The fox and the rabbit are most frequently encountered as figures into which witches change from among wild animals. Equivalents may be looked for and similar beliefs demonstrated in the West.

The extremely wide strata of beliefs about witches extend to every area of life, but to speak very generally, the majority belong to the category of bewitching with the Evil Eye (rontás) (cf. p. 685). Thus witches harm small children by the Evil Eye, and break up or bring together young couples as they wish. They might bring sickness on man and beast equally, cause damage to the crop, and secure the yield of animals for themselves. However, a witch would be compelled to bow to and withdraw in front of one with greater knowledge and power.

Such a person could be, as was considered especially in the Great Plain, a Cunning Shepherd (tudós pásztor), who could defend not only his own stock and his interests with supernatural power, but also tried to help others and to fend off the bewitching of witches (cf. p. 675). A Cunning Shepherd, similarly to witches, also acquired his knowledge in an active way, at the crossroads or by the acceptance of some kind of a herdsman’s tool–a cudgel, satchel, or ringed whip–or by a handshake with an older wise herdsman who was dying.

The Cunning Shepherd had power over the stock in every respect. If he wished, he was able to scatter the flock of others, so that the animals wandered off to several days’ walking distance, but if he climbed his special tree and called the beasts back, then they returned even from several days’ walking distance. A shepherd of lesser knowledge could not scatter the stock of the Cunning Shepherd, because on the Day of St. George he had encircled the pasture and fold of his own with smoke so that his cattle could not break out. The power of the herdsman was thought to lie in his cudgel and in his whip. The skin of a snake that had come out on St. George’s Day was braided into the latter, because it gave them power over the stock.

{676.} Cunning Shepherds as rivals often set two bulls against each other. The shepherd of greater knowledge was either protected by a circle of smoke, or tamed his attacker with salt poured out on a hat. At such times he could turn the bull around to chase or even destroy the one with lesser knowledge. A runaway herd of horses could be brought back from great distances by beating on a szűr spread on the ground.

Herdsmen were forever in a state of feud with witches, especially for bewitching cows and taking away the milk yielded. Not only were they able to discover who had taken the milk away, but by beating the milk with a hatchet, by smoking one garment of the bewitcher, and by other methods, they forced the person to appear on the scene of the witchcraft and somehow repair the damage done. A Cunning Shepherd was able to cure his own stock and the stock of others by both practical and supernatural methods. He had knowledge of many crafts, among others, how to bind by supernatural power (kötés) or to release (oldás).

The latter is the most characteristic attribute of the Clever Coachman (tudós kocsis) (cf. p. 590). A Clever Coachman gained his knowledge with the help of some kind of implement. Thus a horseshoe nail or a magic whip assured supernatural power, which could, however, only be purchased for a symbolic sum. The main power of a Clever Coachman was to halt and bind horse carriages, but he could also reverse this no matter who had done it, he or someone else. At such times the Clever Coachman hit a spoke of the wheel with his hatchet, or struck the end of the carriage beam with an axe or a wine bottle. At other times, with the button tied to the tip of his whip, he struck out the eye of the horseman who had bound his carriage, even though he was at a great distance, thus freeing his carriage to go on. If the situation required, he was able to rise up in the air with his horses and carriage, and if on the way the horse died of the great strain, he could still go home with it, and the horse dropped out of harness only when they reached their destination.

One interesting feature of the Clever Coachman’s knowledge is his power to turn a straw mattress into a horse and start out on the road with that. We can suspect the elements of certain pre-Conquest shamanistic procedures in this as the skin of a sacrificed horse was stuffed with straw, so that it could come back to life and be at the disposition of the dead in the other world. The most polished, well-rounded myths developed in the region east of the Tisza, especially around the figure and activities of the Clever Coachman and Cunning Shepherd (cf. p. 591).

The millers were also thought to possess supernatural power. The knowledge of sending and chasing away rats was attached to them throughout the entire linguistic region.

Faith in the power of “seeing women” (léleklátó asszony) and healers (javasember) lives on almost to this day. Their activity is manifold. Thus there were some who could make contact with and transmit messages to the spirits of people who had died in the near or distant past. People came from far away to consult certain highly reputed seers (látóasszony), especially during wartime, when they wanted to find out something about their dead or missing relatives.

There were among them some who achieved cures with prayers and incantations, while others practised the art of divination. Although the {677.} majority of such persons were strongly religious, in the 20th century they came into conflict with both the Church and secular authorities. Some of these persons were supposed to have acquired their supernatural knowledge during sleep, during “hiding”, just as the táltos did, a fact which demonstrates how the oldest forms of belief continued to exist among newer circumstances.

The characters listed above are all persons who belonged to some community, or at least appeared there from time to time. What differentiated them from average, everyday people was only that in one or another area of life they commanded supernatural power and used it for good or evil purposes, for the benefit or the ruin of themselves or of others. However, there exist also some truly supernatural figures in the world of Hungarian beliefs, although their number is significantly smaller.

The origin of the Hungarian word lidérc (Ignis Fatuus incubus) has not yet been successfully resolved. Many characters, and accordingly many different kinds of Eurasian beliefs, are concealed in the figure. Thus it can mean a special kind of lidérc chicken, hatched by someone from an egg held under his armpit. This will acquire everything its master wishes to make him rich, but it may also endanger his health. Furthermore, as long as it is alive, its master cannot free himself from it, or can do so only with great difficulty. In some places lidérc means a lover who appears in human or animal form and destroys a man or woman, often by tormenting him or her to death. Finally we also meet with its meaning as will-o’-the-wisp, usually wandering, like a dead spirit who for some reason cannot come to rest, over the area where at one time he had lived.

The belief in the ghost of a Wandering Surveyor (bolygó mérnök) is connected with the lidérc. The surveyor falsely measured the land during his life, cheated the poor people, and this is why he cannot rest. He walks the fields with a lantern and a measuring chain, remeasuring the land that has already been divided. Because he has no help, he must run from one end of the land-measuring chain to the other. They believe him to be generally friendly, but if somebody meets him directly or hinders him in his work, then he hits the man in the chest with his lantern.

It is traditionally held that the soul of the dead man leaves his body but still wanders about the house and watches to see if the burial (cf. pp. 627–37) takes place in an orderly fashion. Afterwards the soul stands in the cemetery gate until it is relieved by another one, at which time the soul is finally freed. But according to folk belief, this does not happen in the case of every soul, because there are some who cannot rest, and return from time to time. The reason may be that the person had not bidden goodbye to his relatives or had some other affairs on earth to be disposed of. And he who was miserly in his life, who had cheated or stolen and in general caused losses for others, or he whose requested things had not been put in his coffin, was also believed to come back. A soul cannot rest if its small children are ill-treated or if the heirs cannot agree on the division of property. At such times it returns, turns everything upside down, and knocks pictures and plates off the wall. The relatives would try to find out the reason for its return, but if they failed, they dug the body up, turned it over, and nailed it with a long nail to the bottom of the coffin.

{678.} The ghost is a soul who for some reason is condemned to wander eternally or until it is in some way freed from its fate. Therefore, the Palots people, when they met such a ghost, greeted him the following way:

| “All souls praise the Lord!” |

Amidst great sighs the wandering soul answered:

| “I would praise Him, too, if only it were possible!” |

Then it wailed in a voice of pain, since it forever has to haul along that boundary stone he once moved further, in order to enlarge his plough land:

| “Oh so heavy! Where am I to put it?” |

| “If it’s heavy, put it back where you found it!” |

If the ghost did so, then under fortunate circumstances, it was freed from the curse and found peace. A ghost could appear in many forms. Most frequently, it haunted people in the shape of a horse, calf, piglet, rabbit, dog, cat, or goose. In most cases these ghosts are of good will and do no harm; at the most, the ghost follows those who get in its way and appears in the shape of a familiar man or woman asking for a ride on a cart; but the cart can then go no further, because it cannot carry the great weight, while the horses, sensing the ghost, run wild. A ghost might appear in a familiar shape leading his victim into a swamp or river to meet his death. This meaning is hidden in the Hungarian word kísértet (ghost), which through the metastasis kísért (haunt) can be traced back to the Ugrians.

The Székelys’ Wild Girl (vadleány) belongs to the group of ghosts having a female form. It is called Fair Maid (kisasszony) in the rest of Transylvania and in the Bodrogköz. In the latter region, they believe her to be generally good-natured. If one does not speak to her, she just walks about quietly and perhaps sits up on a cart. However, if they oppose or taunt her, or perhaps swear in front of her, then in her anger, she breaks everything she finds in her proximity. In the Transylvanian version, it is even possible to capture and marry her, and she also lures men.

Many more less frequent figures, or figures not occurring in a larger area, could be mentioned among the characters of the world of beliefs of the Hungarian peasantry. In general, we can observe that among these, dwarfs, giants, fairies, elves, water sprites, house spirits, and others, all of which are fairly frequent among the surrounding peoples and especially among peoples to the west of us, occur relatively rarely.

| The World of Hungarian Folk Beliefs | CONTENTS | The Peasant World View |