| Collective Work and Social Gatherings | CONTENTS | The Churches and Religious Life |

{101.} Self-governing Bodies of the Village

Having discussed the smaller parts of the inner structure of the Hungarian village, we move on to the larger structure which extended to everything and everyone in the community. Needless to say, this larger organization bore the marks of elements borrowed from the outside, but there are also those the inhabitants created for themselves or else adapted to their needs.

The leader of the village, the bíró, possessed different jurisdictions and tasks at various periods. As the original meaning of the title hatalommal bíró (possessor of power) indicates, the administering of justice was the most important role he played. We find that the precursor of the office appeared simultaneously with the development of the Hungarian villages, beginning in the 11th century. His task was to uphold order in the village, to collect taxes, or rather to promote taxes, and, furthermore, to judge petty cases. According to local need the legal customs of certain settlements were set in village laws from the end of the Middle Ages, and the village mayor guaranteed the upholding of these.

1. Tápé, Csongrád County. 1641, 2. Kislőd, Veszprém County. 1841, 3. Magyaralmás, Fejér County. 1788.

Election of the village bíró counted as one of the biggest events of the village, since much depended on not only who the new mayor was, but also on what family or clan he belonged to. In the early morning the village drummer or kisbíró announced the place of the election and the names of the nominees. The retiring mayor asked the pardon of those whom he had in some way offended since he came to office and at the same time made a suggestion in regard to his successor. Only the members of the magistracy elected the mayor, either by popular acclaim or by voting by name. The outgoing village mayor handed over to the new one the village staff (bíróbot), the key to the village chest, and the village seal. This was followed by the election of the officers for smaller posts. Finally they all accompanied the new village mayor to his home, where he invited the members of the council and the more prosperous and influential gazdas in for a toast. At some places they planted a tree in front of his house to commemorate the election. At this time they carried the pillory there from the house of the old mayor, symbolizing with this that the meting out of justice has changed hands.

During the second half of the last century the course and jurisdiction of village mayoral elections were standardized nationally. Mayors were elected every three years, and for this the high magistrate of the district nominated three men. The citizens could vote for the one most suitable to them. Naturally the nominees came from among the most prosperous gazdas and from among those whom the leaders of the district and of the country knew would represent the interest of state authority. The mayor’s task extended to three areas. He directed the autonomous management of the village and carried out the decisions of the council and the magistrate. Secondly, he enforced the decrees and laws of the country and the state in the village. Finally, he acted as judge within {102.} a relatively limited circle, which extended mostly to stealing from the fields, disturbances of the peace, settling smaller property suits, and regulating the disorderly.

Other deputies also carried out specific tasks in the handling of smaller transgressions. Thus we can frequently find references to törvénybíró (law judge), mezőbíró (field judge) and other assignments in memoirs and notes. Besides these, from the Middle Ages on, two to ten esküdts (jurymen), were selected according to the size of the settlement, for the direct assistance of the village mayor. As they were familiar with all the problems of the village, later village mayors emerged from among them. Generally, one of them always had to stay at the village hall, to record the complaints and to notify the mayor if the question at issue came under his jurisdiction. He participated at the execution of distraints, and made suggestions in the affairs of the poor and in helping them.

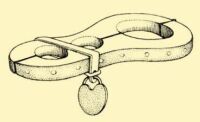

The kisbíró (village drummer) was the permanent employee of the village who was on duty all day, and for this he got a certain amount of payment in kind and clothing. From the end of the 19th century, this was changed to cash in more and more places. He had to call clients to the village hall and deliver notices. Drumming was his most important task, followed by his reading news of common interest and calls for marketing, repeated at various points of the village.

Szentistván, Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

In every village, there were also night watchmen (éjjeliőr or bakter), who received a pre-determined payment in kind, clothes and boots. There were at least two, but in larger settlements, sometimes more. Their service started in the evening with the lighting of lamps, and ended in dawn. One always stayed at the village hall, while the other made a tour of the village, and as a sign that he was fulfilling his task {103.} satisfactorily, he blew a horn each hour and sang, or recited verses. It was among his tasks to address strangers and those coming around late, to inspect taverns, and to prevent thieving. He took the captives to the town hall and locked them up in the jail. He was responsible for his work directly to the village mayor. The fire watchers (tűzőr) watched the village night and day, from the tower of the church, and in summertime they kept an eye on the outlying fields as well. If they detected a fire somewhere, they set the bells ringing irregularly, a sign of fire, and signalled the direction of the flames with a flag or a lantern.

Nagyszalonta, former Bihar County. Second half of 19th century

The village bíró, the jurymen, and the members of the magistracy represented the village to the state. A distinguished place was due to them at church, weddings, and all sorts of other gatherings. They represented the interest of the village in questions which affected several villages or perhaps the entire district at once.

The common lands that were not divided among the gazdas of the village and were intended for various purposes were handled communally, often by the pasture association (legelőtársulat), found in almost every Hungarian village. This association was especially important, because after the liberation of the serfs, the landlord gave the serfs (if he gave at all) a part of his pasture in one piece. This land was not divided; instead, it was shared by each land-owning former serf, according to the size of his arable field and the number of animals he kept. Thus the cottiers, the predecessors of poor peasants, and the rural workers were deprived of pasture, or else, in some places, they had to pay a high price for the right to let their animals graze. The members of the association collected a certain amount of money annually for the upkeep of the pasture, the cleaning of wells, and especially for the wages of the shepherds. Out of this they paid the old gazda, who was later called “president”, and the pasture of farmstead gazdas as well, who directly supervised the order of pasturing. They elected a treasurer and, according to the size of the pasture, other members of the association every three years. The pasture association at the end of the year picked out the herdsmen from among the volunteers who promised to be the most satisfactory. Such herdsmen got, besides their wages, a pre-determined payment in kind for each animal.

The last form of the forest communalty (erdőbirtokosság) also developed after the liberation of the serfs, when the forest lands of the landlord and of the peasants were separated from each other. They kept the latter together also at the insistence of the state, since their division would soon have led to the complete destruction of the forest. The proportion of the shares was divided according to the size of the property in land, and it was possible to buy and sell this share independently. Such forest rights assured a share in the profit of tree felling, or its adequate equivalent in kind, to the owner. At the head of the forest communalty stood the president, formerly the forest bíró, who with the help of the gazdas, but always on the basis of a majority decision, decided about cutting, new planting, and the amount of contributions. The work of the forest bírós was inspected and directed by the organs of the national forest administration, but in spite of it, these forests did not reach the level of the national forests and those that belonged to the landlords.

| Collective Work and Social Gatherings | CONTENTS | The Churches and Religious Life |