| The History and Present-day Organization of Hungarian Ethnology | CONTENTS | Hungarian Ethnic Groups, Ethnographic Regions and Pockets of Survival |

The Ethnogenesis of the Hungarian People and their Place in European Culture

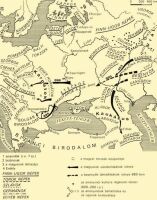

The Hungarians constitute the largest group of the Finno-Ugric language family, followed in numbers by the Finns, then the Estonians and some other smaller and larger groups in the Soviet Union. Based on the testimony of linguistics, archeology, the study of plant and animal species and other sciences, the original home of the Finno-Ugric peoples has been located west of the Volga–Kama region, where they lived in the near vicinity of each other until about the third millennium B. C. These fishing-hunting peoples, according to the evidence of archeology and linguistics, already practised husbandry and even primitive agriculture before they began to disperse. The Hungarians were located in the original homeland near the Voguls (Mansi) and Ostyaks (Khanti), together with whom they created the Ugric branch, but the vocabulary of Hungarian shows that they also maintained contact with the Permian branch. Very little remains for posterity from the material culture of the Finno-Ugric and Ugric period. Here and there in the area of fishing and hunting we can suspect some inheritance in certain tools or methods of procedure. There is more of this early cultural stratum hidden in the intellectual culture. In lamentations and in certain carols, in children’s games, in the beliefs about the soul, and in shamanism, there occur certain elements of Hungarian ethnic history which are traceable to its early phase (cf. also pp. 670–72). The Ugrians (the Voguls, Ostyaks, Magyars) separated slowly in the middle of the third millennium B. C. from the Finn-Permian branch (the Finns, Estonians, Zyryans [Komi], Votyaks [Udmurt], Cheremissians [Mari], Mordvinians, Lapps, etc.).

{27.} The separation of the Magyars and the later Ob-Ugrians (Voguls, Ostyaks) must have taken place between 1000 and 500 B. C. The so-called Ananyino culture, to which presumably the pre-Magyars also belonged, existed during this period. By then they were building earthworks, and their tools made of bone have remained in large number. The ancient Magyars, pushed from the Volga–Kama region towards south–south-east, emerged from the forest belt into the world of the wooded steppes.

Not only did the land change around them, but they also came into contact with newer, largely Turkic peoples. Thus they learned the most {28.} important branches of animal husbandry: the domestication of sheep, cattle, and horses. They were nomadic during the period of pasturing. At this time they also became acquainted with the basic elements of plough agriculture, which presupposes a partially settled existence. Their contact with the Turkic peoples must have been strong, because Byzantine sources in the beginning called them Turks, and other sources mention them also by a Turkish name, calling them Onugrians, ten tribes. The naming of our people in most European languages derives from this word: (H)Ungarus, Ungar, Vengri, etc., while the Hungarians call themselves Magyars after the tribal name Magyer of Ugrian origin.

During the move southward the Magyars reached the foothills of the Caucasus, where, at least from the 8th century, they became members of the Khazar Khaganate. This empire, possessing a well-developed animal husbandry, field, garden and grape culture, already wore the features of a nearly feudal state and in this the Magyars also participated. In the 9th century seven Magyar tribes, also joined by one Khazar and a rebel Kabar tribe, moved on towards the west and occupied the large territory that stretched to the Lower Danube. By then even the Byzantine sources called them Magyars. They were engaged not only in nomadic husbandry, but in agriculture as well, and settled mostly along the river in semi-permanent dwellings.

The traces of contact with the various Turkic peoples can be shown primarily in the characteristics of husbandry, especially nomadic animal husbandry, in the plough cultivation of fields, and in vine growing. Some characteristics can be found in building construction and in clothing as much as in the processing of hemp with certain implements that remind us of these peoples. In the area of folklore, many elements survived almost until the present day, though they might show up in different structures. Examples are the learning of a kind of runic script and the expansion of shamanism, the major characteristics of which are preserved in the person of the táltos (shaman). The trail of pentatonic melodies, characterized by the exact repetition of the melody a fifth lower, can be followed through the Turks to Inner Asia, and this type of melody constitutes about ten per cent of Hungarian folksongs. We can also find traditions referring to this period in the range of customs relating to weddings and burials.

It was in South Russian territory that the Magyars first met different Eastern Slavic tribes, such as the Poljan and Severjan, from whom, instead of the Khazars, they collected the taxes. They warred with them and sold the prisoners to Byzantine merchants at the Black Sea port. Their contacts left imprints not only of wars but of peace as well. They gained additional knowledge of fishing, and became acquainted with the tools and methods of group work. Their agricultural knowledge also expanded; they probably learned the use of the wheeled plough from the Slavs. Some elements of their body of beliefs, e.g. relating to witches, also originated from this period.

The warring, nomadic groups of the Magyars broke into the Carpathian Basin from 862 on and interfered in the conflicts of the peoples who lived there. At this time the head of the Magyar tribal confederacy {29.} went to war with about 20,000 horsemen, beyond which we must suppose a body of people adequate to support them, so that the number of families must have numbered at least 100,000, and the total numbers reached and possibly exceeded half a million.

The Magyars, while helping the Byzantines, defeated the Bulgarians, who in turn took revenge by releasing the Pechenegs who pushed from the east against the Magyars just at the time when their military force was roaming far afield. On seeing the devastated settlements and fearing renewed attacks, the entire confederacy of tribes realized that there was nothing else to do but to push into the Carpathian Basin. This they did and in the course of a few years they had occupied it.

The Carpathian Basin, throughout its history, has given a home to many peoples, some of whom passed on their culture to their successors. Such were the Celts (4th century B. C. ), who were known as the disseminators of iron tools. Then came the Romans, who left behind in Transylvania (Dacia) and Transdanubia (Pannonia) such a culture that even the centuries of the period of migration could not sweep away certain of its elements.

The Magyars found many different kinds of peoples in the relatively sparsely populated Carpathian Basin. The Bulgarians had settled on the central great steppes and a part of Transylvania. At other places different Slavic peoples had settled in pockets: Moravians, Danubian Slovenians, White Croatians, Slovakians, and others. A remnant of the Frankish rule of Charlemagne, Bavarians lived at the western boundaries. Only one substantial state stood in the way of the Magyars, the Moravian principality, stretching from the west to the Garam, but this too they defeated. The conquered peoples adjusted to the Magyars, but the Magyars also adapted themselves to them and so began the interaction of Magyar and Slav that continues even today.

For more than half a century the contact of the Magyars with Europe meant war, with roaming and marauding to the west. They exploited the dismemberment and eternal warfare of the feudal West. They attached themselves to one or another ruler and fought in Italy, Germany, and got as far as Switzerland, France, and on one occasion even Spain. The head of the tribal confederacy looked favourably upon such military excursions, not only because they helped to keep the military force fit, but also because the practice held off western attacks while he was organizing his own country. The speed of the Magyar light cavalry, their terrible arrows, and their new fighting method not only brought victory, but also gave rise to general fear in Europe, until the united German armies indicted a decisive defeat upon them at Augsburg in 955. In the course of their roaming the Magyars looked at a completely different and for them new world; they met the new and for them strange European culture.

However, this did not basically change their half-settled, half-nomadic way of life. The change took place at the time when, following efforts made by Byzantine missionaries, King Stephen I (997–1038) took up Roman Christianity. He urged, and occasionally forced, the entire Magyar nation to do the same. By this step the Magyars avoided attrition, which had led to the disappearance of many peoples during the {30.} period of migration in the Carpathian Basin. They retained their language and their independence, but a large part of the culture, the world of beliefs and the customs they brought with them vanished, changed, or were amalgamated with other cultural elements.

Ultimately, Christianity came to the Magyars through Slavic mediation. Accordingly, they were acquainted with a great many new words, concepts, objects, and phenomena. Some examples are: keresztény (Christian), pap (priest), barát (friar), apát (abbot), apáca (nun), szent (saint), pokol (hell), csoda (miracle), malaszt (divine grace), vecsernye (vespers); some of the names of weekdays: szerda (Wednesday), csütörtök (Thursday), péntek (Friday), szombat (Saturday); and among major holidays, karácsony (Christmas). The Magyars also became acquainted with the new social order primarily with the aid of the Slavs: császár (emperor), király (king), ispán (bailiff), tiszt (officer), kenéz (magistrate), udvarnok (Lord High-Steward), bajnok (champion), and a string of other concepts. However, from the point of view of ethnology, the influence that affected the Magyars in the area of agriculture is even more important. Significant changes took place in the system of working the soil: parlag (waste land), ugar (fallow), and in the method of cultivation and harvesting. In particular the domestication of garden vegetable production: bab (beans), cékla (beets), mák (poppy seed), retek (radish), uborka (cucumber) can be attributed to the Slavic peoples with whom they lived together. The influence of close ties may be found in many fields: crafts, trades, family relationships, houses, dwellings, nutrition, clothing, and many others. Not all influences were, of course, one-way, as is shown by the fact that in the Slovakian language the words of Hungarian origin approach one thousand. New concepts and new attainments were linked to these expressions.

Contact with the Germans at the western border region had already begun at the time of the conquest of Hungary. This was especially strengthened in the time of Stephen I, who brought in and settled Bavarian–Austrian knights, priests and burghers. However, already during the 12th and 13th centuries peasants and artisans whose descendants are still living in the region of Szepes (Czechoslovakia) and Transylvania came in much greater numbers. This influence affected primarily city life, the guilds and trades, but also certain new objects and concepts reached the peasantry (tönköly [German wheat], bükköny [vetch], csűr [hayloft], istálló [stable], kaptár [beehive], major [farmstead of an estate], puttony [butt], etc.), which seem to indicate development toward more intensive farming.

The Hungarians soon came into contact with Italians also, but Italian influence was much less compared to Slav and German influence. Some of the technical terms of navigation (sajka [small boat], bárka [bark], gálya [galley]), and of commercial life (piac [market]) left marks mainly on city culture. Buildings of Italian masters who worked here (churches, forts, castles) transposed European forms of architecture into peasant styles. The turn of the 12th and 13th centuries saw significant French and Walloon settlements. Besides priests and monastics, peasants came too, who left clearly visible marks in areas such as viniculture.

Slavic, German, French, and other Western influences can be traced {31.} not only in the material culture but in the folklore as well. Amongst the ruling classes the great cultural change came earlier, but it gradually became observable among the peasantry also. One of the transmitters of the new culture was the Church, which introduced a completely new intellectual culture to the Hungarians through its liturgy, its saints and the associated legends, and through customs connected with church holidays. In the courts of the king and the high nobility, western heroic songs were propagated by bards, while the one-time pagan bards were driven back among the people, and the priests cruelly persecuted them along with the memories of the old world of beliefs. The separation of the epic literary forms slowly began at this period. Side by side with heroic songs now legends, myths and ballads began to play an increasing role. An early stratum of the ballads very likely came to the Carpathian Basin with the Walloon-French settlers. The folklore of the Hungarian peasantry, while retaining many elements from the previous period, slowly set out on the European road. That this change did not take place without a jolt is shown by the recurrent pagan rebellions, but the ever-strengthening economic and intellectual process proved irreversible.

All this was supported by the fact that Eastern political ties, although not broken completely, became significantly weaker. The kings of the House of Árpád (until 1301) still maintained their ties, primarily based on kinship, with Kiev and Byzantium, which represented Eastern Christianity, but it was no longer an economic and cultural influence touching upon the entire nation.

In 1241–42 the Tartars destroyed a significant part of the country. The nomadic Cumanians and after them the Jazygians appeared at this time on the country’s central, flat areas, well suited for extensive animal husbandry. This meant the strengthening of the pagan tradition in the second half of the 13th century, since even some kings (Ladislas IV, or Ladislas the Cumanian) revered ancient customs. However, during the next centuries the Cumanians and Jazygians assimilated into the Hungarians, whose social development represented a higher stage, and so only a few words and objects were accepted into the Hungarian language and culture (buzogány [mace], csődör [stallion], komondor [sheep dog], balta [hatchet], csákány [pick ax]).

The bulk of the Hungarians were working people divided already in the Middle Ages into several social groups, more or less differentiated from one another. The situation and living conditions of servants, of permanent or free serfs, freemen (szabadok) and the artisans changed in every era. A ninth of the produce was paid to the landlord for their land, and a tenth of the produce to the Church, besides which the people had to do labour service and occasionally give money and gifts. The amount of gifts changed according to what the landlord needed at certain times. In general it may be observed that towards the end of the Middle Ages, the situation of peasants increasingly declined. The result was that the number of local peasant risings, smaller and larger ones, multiplied.

The peasant rebellion in 1514 led by Dózsa was the largest and most notable. After a cruel defeat, the legal rights of peasants were drastically cut back, permanent serfdom was declared, the right to move was {32.} prohibited, and the amount of work due to the landlord was increased to a whole day or two days a week or often even more. Furthermore, all this happened just at the time when the Turkish Empire posed an immediate threat to Hungary. In 1526 the Turks defeated the Hungarian army at Mohács, a town along the Danube; the king, Louis II, fell on the battlefield and the historical period began when the country was divided into three parts. The Turks ruled the central and southern areas, the House of Habsburg acquired the northern and western regions, and in Transylvania a more or less independent principality was set up.

Although this period, which lasted to the end of the 17th century, was one of the most difficult periods of Hungarian history, cultural development did not come to a halt. The great artistic and intellectual currents of Europe arrived and had their full effect here: the Renaissance, Humanism, the Reformation. The printing of books expanded, more and more schools were established. The most difficult situation for Hungarian peasants was within the territories occupied by the Turks, where taxes, ransoms, robberies, and the burning of villages were everyday occurrences. In spite of all this, peasant culture continued to develop even in this period. The three-unit house (room + kitchen + room) spread over a larger and larger territory, and at the same time some pieces of furniture appeared, new in form and function. In those market towns which were spared by the Turks, trade flourished. Even articles of clothing taken over from the Turks (kalpag [hat], csizma [boots], papucs [slippers], dolmány [dolman]) were made, and new foods (tarhonya [granulated dry pastry made of flour and eggs]) were adopted. A large proportion of the cultural goods of Ottoman Turkish origin came to the Hungarians through a South Slavic filter.

In Transylvania peasant culture was shaped by the mutual interaction of the Hungarians, Rumanians and Saxons who lived next to or near each other. The Hungarians supplied agricultural goods, the Rumanians supplied animals, while the Saxons supplied the products of the artisans. The multiplicity of Renaissance style and the influx of Turkish industrial products and their effects on folk culture can easily be traced here.

The population of the country’s northern region became more dense in this period, since primarily nobles, but in part even serfs fled in large numbers to this area from the southern region. However, even in this territory they could not escape the robberies of the Imperial mercenary troops, who often surpassed even the Turks in cruelty. German influence can be more strongly felt here, but it affected the peasantry to a lesser degree.

Turkish occupation had barely ended at the end of the 17th century when the Hungarians again took up arms to free themselves from Habsburg oppression. After the loss of the fight for independence (1703–1711), led by Ferenc Rákóczi II, the Habsburgs gave the most fertile areas of the pillaged and depopulated country to those Austrian–German landlords who earned merit during the war. At this time the migration from north to south began, the result of which was that the Hungarian groups who had previously fled from the Turks to the north, now swarmed down to the Great Plain. Slovaks also settled in the same area. The German influx exceeded even these in numbers, {33.} mainly in Transdanubia, but also in certain areas of the Great Plain and Upper Hungary. Thus, by the end of the 18th century the Hungarians totalled barely fifty per cent of the population. All this again affected Hungarian peasant culture, although only to a smaller degree, because settlement pockets of the various nationalities either assimilated to the Hungarians or took on significant elements of Hungarian culture.

The relative peace of this century, in comparison with those preceding, meant the strengthening of the peasantry, even though their burdens had grown. Beside services in kind, they had to provide the landlords with 52 days of work with a horse each year or 102 days of work on foot, and had also to undertake several days’ long hauling. The inner structure of agriculture also changed: extensive animal husbandry decreased, the significance of farming grew, new crops (potato, maize, green pepper, tobacco) became widely spread. The house and its furnishings developed further, and certain elements of folk customs, which live on to this day, appeared largely then, for the first time. Hungarian folksongs of a new style were formed and the most characteristic dances developed. By the end of this period, which came to an end with the freeing of the serfs in 1848, the characteristic traits of Hungarian folk culture became clearly evident, and may be studied in collections of museums and also in lingering tradition.

The social differentiation of peasantry owning land became increasingly obvious by the second half of the last century. A growing chasm can be observed between the rich peasant who owned 20–50 hectares and the poor peasant who struggled on 1–5 hectares. A greater number of the poor peasants became destitute, and to their numbers may be added those indigent agricultural labourers, the masses of labourers on the great estates, who numbered millions. Special groups emerged amongst such rural workers: seasonal labourers, pick and shovel men, melon pickers, tobacco pickers. Each group has specific traits of culture typical only of that profession. Yet this period, in spite of everything, is the era when Hungarian folk arts flourished. Costumes, homespun and embroidery became more colourful; the supply of new materials from industry was playing an important part in this proliferation. The most artistic products of the potter’s craft and the best painted furniture originate from this period, which by and large closes with World War I. Generally, the richest and the poorest among the strata of the peasantry were first to give up their traditions. The richest did so to make easier their approach to the ruling class, and the poorest out of economic necessity as a result of the basic change in their form of life.

Beginning in 1920, with the breaking up of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the nationalities living in Hungary formed their own states in accordance with the peace treaty, and the present borders of Hungary were drawn up. Within these live 10.5 million citizens, and Hungarian is the mother tongue of 95 per cent of them. Among the nationalities, Germans, Slovakians, South Slavs and Rumanians live in Hungary in larger numbers.

After 1945 the Hungarian nation tried to obliterate the serious wounds caused by the war, and from 1948–49 it has worked on erecting socialist economic life, society, and culture. Of outstanding importance for the {34.} Hungarian peasantry is the year 1961, when following the pattern of a great many earlier examples, they entered the path of collective farming. The past two decades show that for them this was as significant a change of fortune as the change from fisher-hunter to nomadic husbandman, or the basic change in life style and culture after the settlement in the Carpathian Basin, or changes brought about by being freed from the burden of serfdom. The character, organization, and assignment of labour changed decisively, resulting in basic adaptations in, for example, the organization of the family. The individual farm outbuildings are gradually disappearing from beside the new houses, since they are needed less and less. With the change of life style produced by the effect of schools and of the media of mass communication, a new culture is evolving, into which everything worth preserving from the old culture is being built. It follows from what has been said above that our synopsis of Hungarian folk culture relates largely to the past, which is revealed, evaluated, and introduced by both ethnology and historical science.

Besides the 10 million Hungarians living within the borders of the country, there are outside the country a large number of Hungarians, whose mother tongue is Hungarian. Thus there are 406,116 in Czechoslovakia, 520,938 in Yugoslavia, 1,811,983 in Rumania, 164,960 in the Soviet Union (1967–68 data), and about 50,000 in Austria. Beside this there are almost one million in the USA, and approximately half million who live in smaller or larger groups in various parts of the world. From the point of view of ethnological research, the Hungarians living outside Hungary are important not only because of their numbers, but also because as a result of their isolated situation they have often well preserved many old traits.

This brief summary simply is intended to acquaint the reader with the major changes of fortune of the Hungarian people in the thousand-year process of development of its culture. Only in this way is it possible to understand the culture of the Hungarian people, which is built on foundations brought from the East, developed in Central Europe, and connected with general European progress.

| The History and Present-day Organization of Hungarian Ethnology | CONTENTS | Hungarian Ethnic Groups, Ethnographic Regions and Pockets of Survival |