| Meat Dishes | CONTENTS | Drinks and Spices |

Milk and Milk Processing

The milk of cows and sheep have the greatest importance in the diet of the Hungarian peasantry. A few sources also mention the drinking of horse milk, but in the historical period under discussion we know of only rare occurrences of this earlier practice.

Őrség, Vas County. 1930s

Although the Hungarian grey cow gave little milk, the fat content of the milk was quite high. Cows in extensively kept herds were not milked, and the calf could suck as much as it wanted. Only a few milk cows were tied at the farmstead for the needs of the herdsmen, who mostly drank the milk fresh but also processed it in the fashion of yoghurt. In the Great Plain the tarhó is the best known among these, and the Magyars very possibly acquired the method of making it from one of the Turkic peoples before the Conquest. They boil the milk in a large-sized vessel, then let it cool until they can just bear putting their finger in it. Then they mix rennet into it, which is usually nothing else but tarhó put aside from the previous making. After the vessel is closed, the milk sets in a few hours. If they leave it open, the setting time increases to 8 to 12 hours. When it is thick enough for a straw to stand upright in it, it is ready to eat.

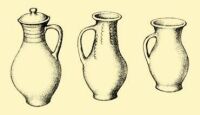

In peasant households, milk is usually drunk fresh. If they pour it into milkpots (köcsög) it sets and becomes sour, and this is much liked, especially in summer. The fat, of lighter weight, rises to the top of the milk and forms cream (tejszín), or to the top of coagulated milk, forming sour cream (tejfel). It still contains much water. When cream is freed from water, it turns into butter.

Szalafő, Vas County. 1930s

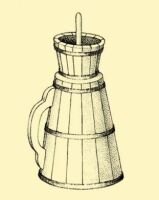

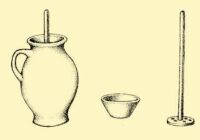

The simplest method of making butter is to shake cream in a vessel until the butter condenses out of it. We find this method both in the western (Göcsej) and eastern (Székelyland) linguistic territories. The equivalent of the old method can be demonstrated primarily among the Eastern Slavs. Various churning vessels made of wood and earthenware, later of tin, spread widely, in which plungers on a shaft are moved up and down until the butter condenses. The left over buttermilk is a favourite drink of children, and what they leave is given to piglets. Making butter is amongst the oldest methods of milk processing, since it is partly Finno-Ugric and Ugric in its terminology (vaj, butter; ráz, shake), partly Bulgarian–Turkish (köpü, churn; író, buttermilk; túró, cottage cheese). If the buttermilk is skimmed and warmed, it becomes knotted and turns into cottage cheese. The liquid is pressed out of it and is then hung up to dry in sacks. Baked or cooked pastries and noodles are filled and flavoured with it.

Szomoróc, Vas County. 1930s

Processing sheep’s milk is usually the task of the shepherds (cf. Ill. 128), who are sometimes assisted by their wives or daughters. The sheep stock of the peasants was guarded by a common shepherd, {297.} and the sharing of the milk developed differently in various parts of the linguistic territory. In the Tiszántúl (Hajdúszoboszló), generally six gazdas put 20 to 30 sheep together into the hands of one shepherd. Everyone got the produce of one complete milking (morning and evening) for a six day period, while the yield of the seventh day belonged to the shepherd. If they put the stock together by tens, that is, if the number of the owners doubled, then the share fell to each person only every second week. In Transylvania the sheep were driven out to the pasture with some celebration on St. George’s Day (April 24). At this time everybody milked his own sheep and measured and marked down the yield exactly. Sharing through the entire course of the summer was based on the first milking. The practice of giving the yield of the milk in rental (árenda) had already spread among the Palotses during the last century. The shepherd gave 2 kg of fresh cheese to the owner for each ewe that could be milked, regardless of her yield, for the entire duration of the milking season.

Kazár, Nógrád County

Sheep were always milked by the men. Milking, broadly speaking, lasted for four months, from May until early September, and yielded 1 to 4 dl a day per ewe. They force the ewes into a tight enclosure, and drive them toward the shepherd. He catches them one at a time, milks each dry, then lets it go. The pail (sajtár) used to be made of wood but now is made of sheet iron. Between its two handles they stretch a string that supports a small mug, into which the milk always goes because it {298.} would otherwise raise too much froth in the big vessel (cf. Ill. 128). The sweet sheep’s milk is not used directly; cheese and cottage cheese is made out of it.

To do this, rennet (oltó) is needed. The Palots shepherds used the stomach of a young lamb or sucking calf. They cleaned it well, salted it, and next day washed the salt out of it and blew it up. They put it away to dry and, when they wanted to use it, cut a piece off, soaked it in warm milk, or maybe poured whey on it, and so could use it by the next day. They did the same in the Great Plain, but there they also dry and store the milk that was left in the stomach of a three-week-old calf.

They let the fresh milk stand for a while, then put as much rennet into it as was needed for the quantity. When it has coagulated, they break it up thoroughly by hand or with a spoon, and again let it rest for a short time in this condition. Afterwards they put it all into a homespun cloth and wring the whey out. In some places it is freed from most of the moisture by means of a press. They make the cheese round (gomolya) in the Great Plain, and in other places they pour it into moulds that give it the most diverse shapes. Finally they further dry it in an airy, but not a sunny place.

Cheese is usually eaten with bread, but in July and August, when the ewe’s milk gets very strong, they make cottage cheese with it. It is crumbled, salted, and kneaded into a wooden or clay vessel and in this way kept for a longer time. In Transylvania and among the Csángós of Moldavia they store it in sheepskin bags, and often even smoke it. Zsendice is made out of the whey that drips from the cheese by adding one tenth of sweet ewe milk to it and stirring it over the fire until it becomes a cheesy, mushy mass. They eat it together with its whey. It was used regularly until very recent times, and was warmly recommended by the peasants as a remedy for tuberculosis.

| Meat Dishes | CONTENTS | Drinks and Spices |