| Underwear | CONTENTS | Mantles and Coat-like Outer Wear |

Outer Wear

Today the difference between women’s and men’s clothing is primarily defined by the skirt or the trousers. The skirt, called kabát in the north-eastern linguistic territory, covers the lower part of the body. Its length varies from above the knee versions (e.g. Buják), through those reaching the mid-calf (Őrhalom), to the ones covering the ankles (Matyós). Several starched petticoats are worn underneath, often as many as ten, in order to appeal to the peasant concept of beauty, a preference for rounded shapes. These are worn with hip cushions for extra roundness. In some regions the skirt is sewn to the bodice or fastened with suspenders which assures not only more comfort, but also makes dressing easier. Skirts are not always sewn together in front. The muszuj or bagazia of Kalotaszeg, for instance, is no more than a back apron, pleated and tied in front (cf. Ill. 199). The apron worn over it covers the front opening. This traditional form of garment indicates how the styles of skirts developed. In many regions skirts were ornamented by smocking, and some women were especially proficient in making these.

The material of skirts may be extremely varied. In Székelyland they make the rokolya out of colourful homespun and the outer skirt out of a solid-coloured fabric. The place of origin of the wearer can be ascertained immediately from the colouring of her skirt. The fabrics produced by small industry have played an important and ever-growing role in the evolution of Hungarian folk costumes from the end of the 18th century on. Artisans known as bluedyers appeared in Europe in the 18th century and used a technique of cloth production brought from East Asia known as batik; it came to Hungary via the Uplands and Transdanubia from the Czech-Moravian, Austrian, and German areas. Within a very short time, bluedyeing workshops of various sizes were in operation throughout the entire Carpathian Basin. There they printed patterns, mostly of western origin, on material which was either their {324.} own or brought to them by the peasants. Various blue-dyed materials began to play an increasingly important role in everyday wear, and even in holiday wear (cf. Plates II, III). For women’s wear on festive occasions, however, especially in wealthy areas or among the more prosperous members of the peasantry, this material became less important as use of manufactured products spread, such as velvet, silk brocade, woven stuffs and other materials, from the middle of the 19th century on.

The apron (kötény) is an indispensable element of women’s wear. It is used on weekdays to protect the skirt, and for holiday wear as well. For this reason, it is one of the most richly ornamented pieces of the Hungarian woman’s costume. The apron also played an important role in the world of beliefs, especially the bridal apron, which the young wife would put away carefully, and keep to cover her sick children with, thus ensuring their quick recovery. The loose apron covers the skirt almost completely, while the narrow apron made of only one width of cloth, covers it only in front. Ornamentation of holiday aprons is extremely varied. There are homespun aprons, but usually aprons are covered with embroidery, and lace and ribbons sewn on their edges. Significant differences are apparent between the aprons of married women and the aprons of girls, mostly in colour, material, and ornamentation.

Women wore a bodice (pruszlik) over their blouses, of which there are two basic types. The older one is shorter than the waist and its neck is more widely cut out. This style has survived longest in the southern part of the Hungarian-speaking territory. The neck is closed on the other form, which extends past the waist. This style was worn in the northern areas. Usually the bodices are richly ornamented, primarily with embroidery and by embellishing the edges in various ways. The diffusion of wearing the bodice can be connected to the expansion of city fashion from the second half of the last century.

Csíkszentandrás, former Csík County. 1930s

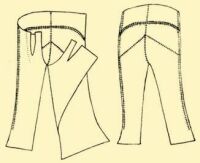

In men’s wear breeches (nadrág) replaced the gatya, or rather turned it into underwear. This transformation of the male peasant costume began in many areas scarcely a century ago and was basically completed by the end of the last century. In many places oral tradition tells us about the first appearance of breeches in the village (e.g. Bodrogköz). They were made of black or blue broadcloth, with a flap in front that folds down. Earlier they were even lined inside. There are also data showing that breeches were worn turned inside out on weekdays and with the right side out on holidays. The breeches of the Székely men, called harisnya (e.g. hose), are one of the most archaic forms (cf. Ill. 16 and p. 361). Their present cut developed from the uniform of the Székely borderguards in the second half of the 18th century. The colour and shape of their black and red braiding mark the social rank of the wearer. The material was generally white, but today braiding trim appears on gray material also.

Men wore a sleeveless waistcoat (mellény, lajbi), made of black and dark blue broadcloth and, less often, of silk. Its characteristic feature is that both its back and front are made of the same material, as opposed to the later version which was worn under the coat. As this later waistcoat can be seen only from the front, it is acceptable to make the back from {325.} cheaper cloth. There are many forms of waistcoats, some with high collars, other with a cut-out neck, some embellished with ornate buttons and braidings. Often ornamental rows of buttons made of silver, tin, pewter and nickel are sewn on. Generally these articles of clothing are among the most ornamental examples of men’s wear.

The belt (öv) is an important piece of men’s wear worn both over and under top clothes. The tüsző or, by its Transylvanian name, sziju, is made of thick leather and tied directly onto the waist. It not only serves as a pocket but also protects the body and keeps it warm. A belt about 3 to 4 inches wide made of thick leather was worn as outer wear in many parts of the Hungarian-speaking territory during the last century. We know they were worn among the Palots people and the Matyó. The widest are the belts worn in Transylvania, such as ones from Torockó, which are embroidered with coloured thongs. Besides securing the garment, such belts also served the function of carrying various objects (tobacco pouch, lighter, etc.) that were hung on them, with the money hidden inside.

We often find ornamental frog closings, braid, and bound buttons, which were made in the shops of the gombkötő (button making) artisans. These embellished the outer wear of women and especially men. In the 17th and 18th centuries these artisans worked primarily for the nobility, but in the 19th century, when the use in broadcloth in folk wear increased, peasants gradually became major customers of braid and button makers. A great quantity of frog closings, braid and buttons appeared on pants and waistcoats, but by the beginning of the 20th century, this old craft which had been indispensable to Hungarian fashion was eclipsed and it finally disappeared altogether.

| Underwear | CONTENTS | Mantles and Coat-like Outer Wear |