| Processing Wool | CONTENTS | Elements of Folk Costume |

{312.} Processing Skin

The processing of skin is an extremely old craft, though it became partly specialized early in the case of certain articles of clothing. Herdsmen have preserved most primitive methods and processes of skin preparation almost until the present day. Herdsmen primarily tried to make use of the skins of animals that had perished. Among various herdsmen, shepherds best understood the preparation of skin–sheepskin naturally–out of which they made many simple articles of clothing. Around the Hortobágy the method is to carefully scrape from the flayed sheepskin, which was then stretched out and dried in a shady place. If very dirty, it was washed and dried again. Afterwards it is smeared thoroughly with a mixture of salt and alum, bran is sprinkled on it, it is folded, and put away. After a few days, the skins are crushed, simply by hand, or softened by pulling it to and fro over a blunt scythe-blade. In the course of this work chalk dust or flour is sprinkled on the skin from time to time, from which it becomes completely white. A dye may be brewed out of Brazil wood, oak-apple, gall and vitriol. This is smeared lukewarm onto the skin, which then takes on a beautiful black colour as a result.

Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

Bács-Kiskun County

Kézdivásárhely, former Háromszék County. 1930s

A similar method of processing used for leather was also practised earlier by Hungarian tanners, whose products were mentioned {314.} appreciatively even by French sources in the second half of the 18th century (Diderot, Encyclopedia, Paris, 1772). Their method was as follows: they removed the hair from the flayed skin with a knife, without any kind of chemical interference. Thus the roots of the hair remained in the skin and made it more compact and resistant. It was worked over thoroughly and trampled on with a salt and alum solution. When this had soaked completely into the skin, it was dried, at first in the shade, then by holding the skins over warm embers. By this means the pores expanded and easily soaked up the hot tallow smeared all over the skin. This method was used primarily on ox-skin, which as a result, turned white. Tanning took only 2 to 4 weeks, as opposed to the tannic method used generally in Europe, which in many cases required up to 3 or 4 years. This fact, and the more compact leather made by this method of processing, made it the preferred method in Western Europe also. This process was practised primarily in Central Asia, in the Near East, as well as in the southern part of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. On the basis of this it may be supposed that the Magyars were already familiar with this method of leather processing before the Conquest.

Great Plain. Second half of 19th century

Sárrétudvari, former Bihar county. Around 1940.

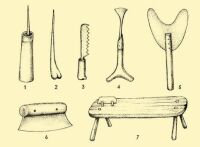

1. Awl. 2. A bone for picking holes. 3. Knife to scratch with. 4. Utensil for stretching out leather. 5. Iron implement for softening leather. 6. Knife for cutting off the flesh. 7. Long bench with a knife for softening leather

Beginning with the Middle Ages tanners used another method. They thoroughly smeared the soaked skin with lime and kept it in that manner for 2 to 3 weeks. After this the hair or wool could easily be removed. They collected the wool, washed it and sold it to the guba makers. The meat and epithelium were carefully removed from the hide which was steeped for a while in a liquid made from chicken manure. After this preparation the tanning (cserzés) followed, the basic material of which was the stripped and crushed bark of oak trees and gallnuts. The hide was kept in this liquid steeping solution for the necessary length of time, to which was added more tanning material every day, so that the acid would stay at the same level. When the cut hide turned yellow inside, the tanning process could be completed. Tanning was followed by a brief {315.} drying, then by treating the hide with fat and then by dyeing it. This method of processing is characteristic of Europe, South Asia, and Asia Minor, but it became increasingly generally used in Hungary also, and replaced the other method.

One of the plants used for tanning especially in Transdanubia around the Balaton was fustic (Rhus cotinus, szömörce), supposedly propagated by the Turks. This is demonstrated by the fact that the person who works with it is called tobak, which is the equivalent of the Ottoman Turkish word meaning “tanner”. This plant assured a good quality of tanning. The finest boots were made out of cordovan leather.

| Processing Wool | CONTENTS | Elements of Folk Costume |